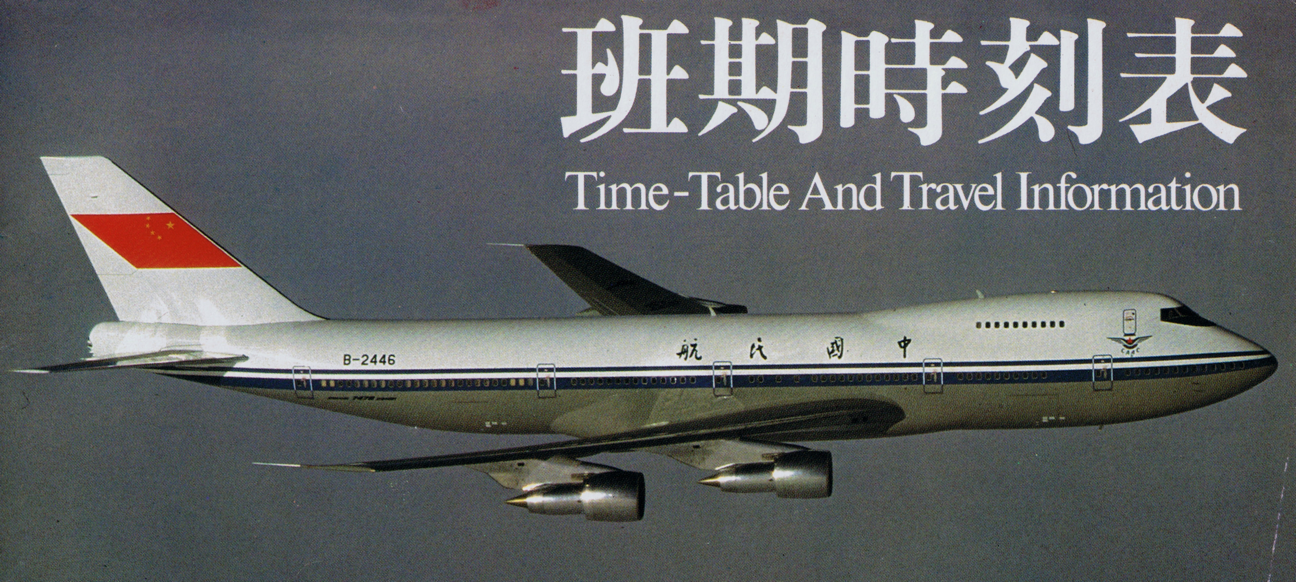

Cathay Pacific - 1967 History Booklet

/Hong Kong's position as a British colony provided a secure and sound legal and monetary position for trade to flourish - and with it, the need grew for frequent service to East Asia's other key cities. Great Britain carefully controlled its airlines after World War II, with its key carrier BOAC (British Overseas Airways Corporation) taking the most important routes, such as the corridor from London through other former colonies in the Middle East and India to reach Hong Kong, and then to points beyond such as Tokyo.

So while Cathay Pacific was allowed to form, acquire a competitor, and even bring on modern jets, the authorities in London kept the carrier bottled up in its home region, unable to reach backwards to Europe or forwards across the Pacific.

This colorful 1967 history booklet produced by Cathay gives its short, two-decade story:

While Cathay desired longer routes, the Convair 880 jet fleet lacked the range to reach much beyond Tokyo or Singapore, nor could it carry economical amounts of cargo. While BOAC had abandoned the Hong Kong-Australia market, the 880 was simply not able to help Cathay grow.

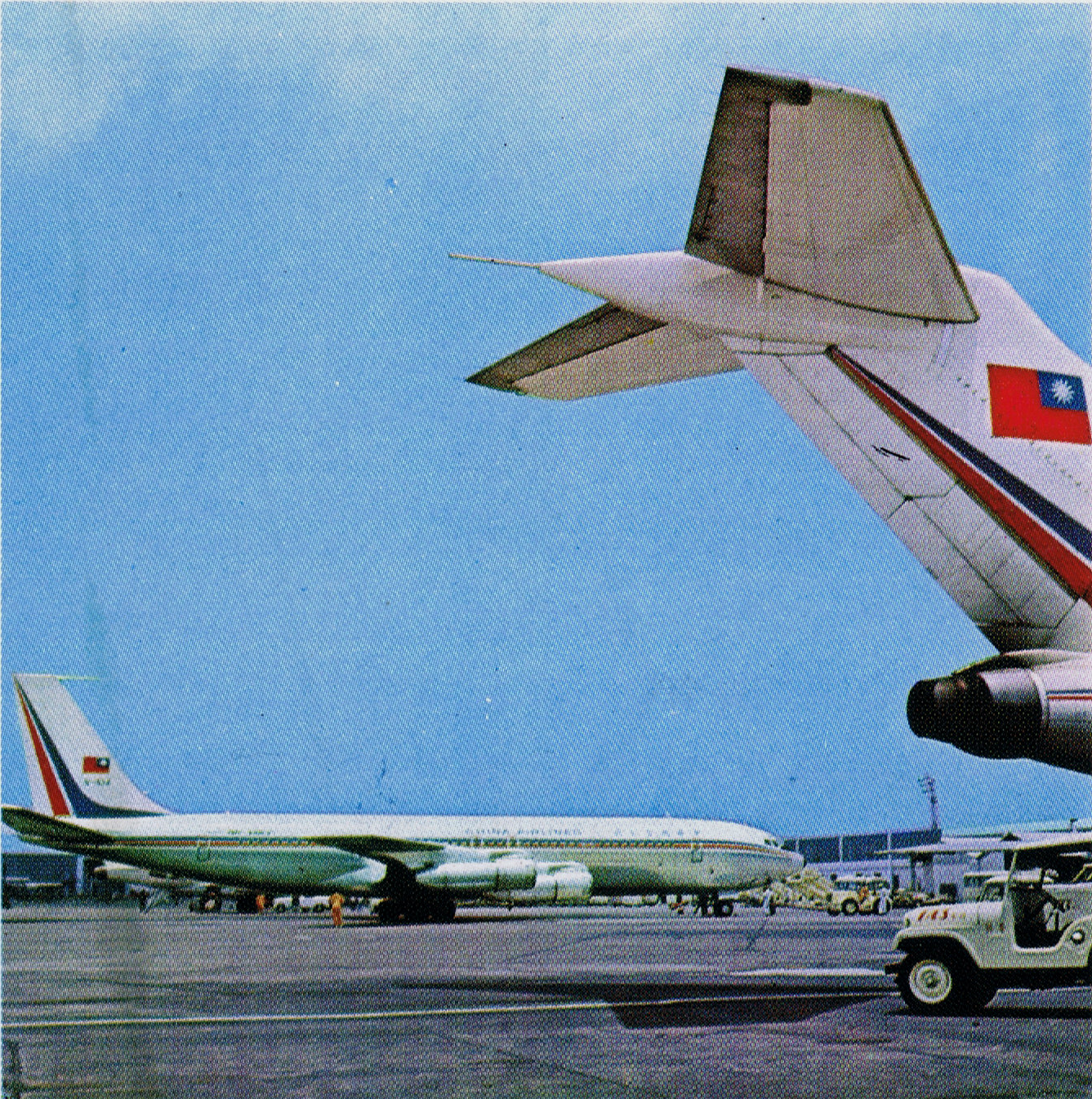

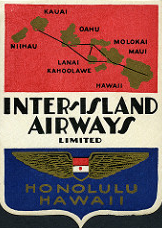

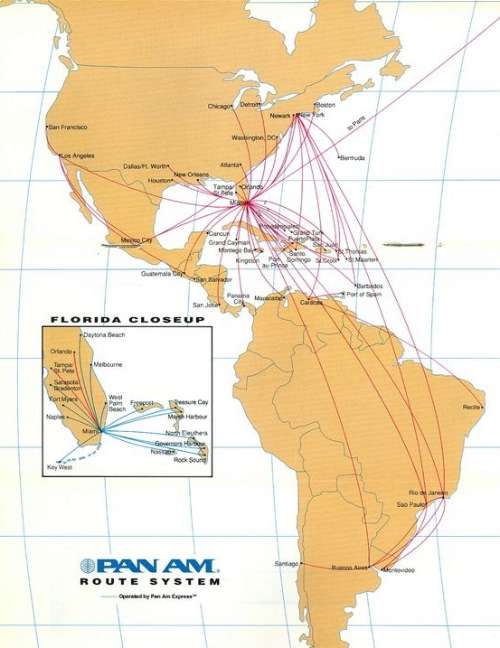

The brochure ends with this compact route network, just as Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos were to fall under the cloud of war:

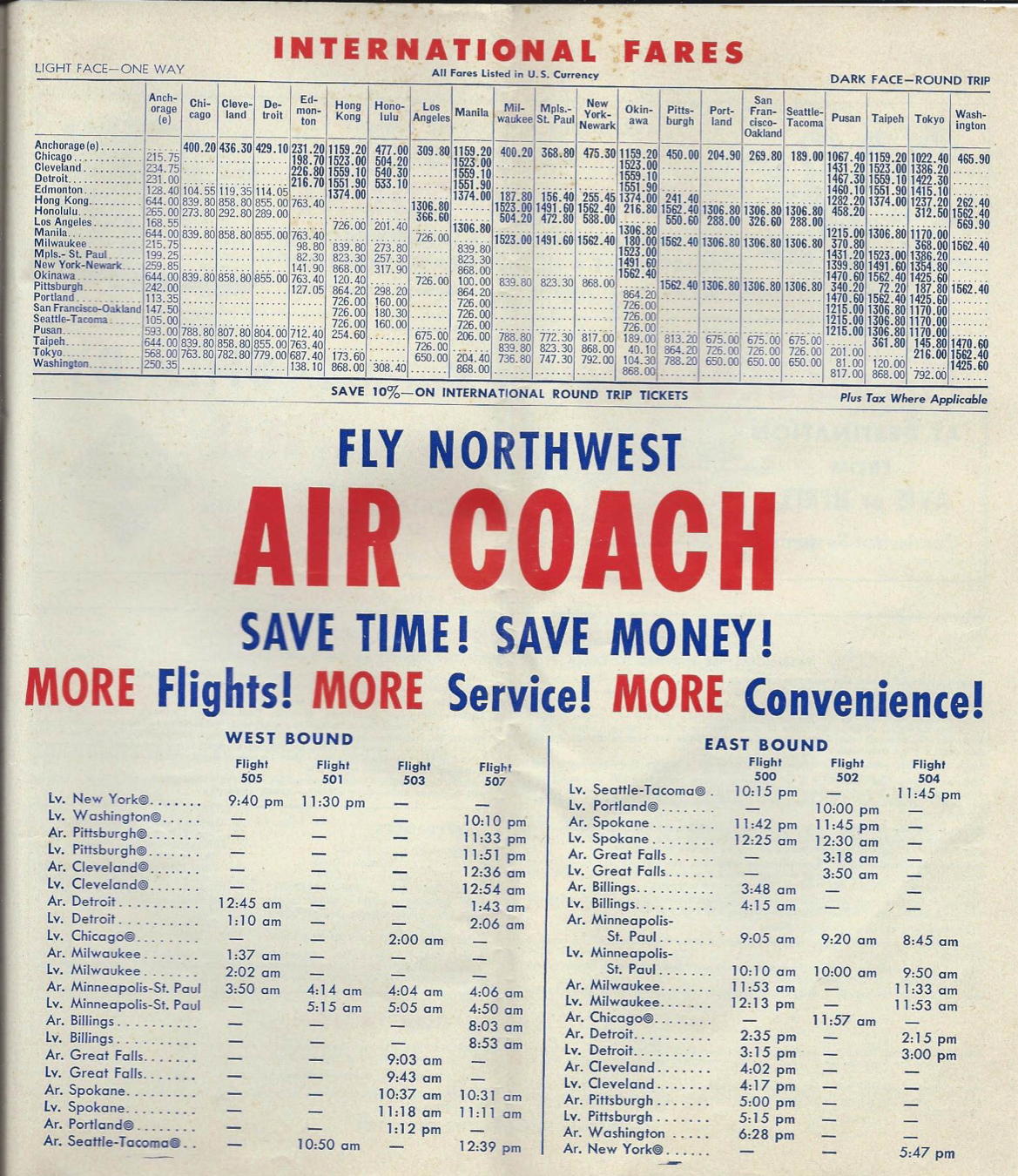

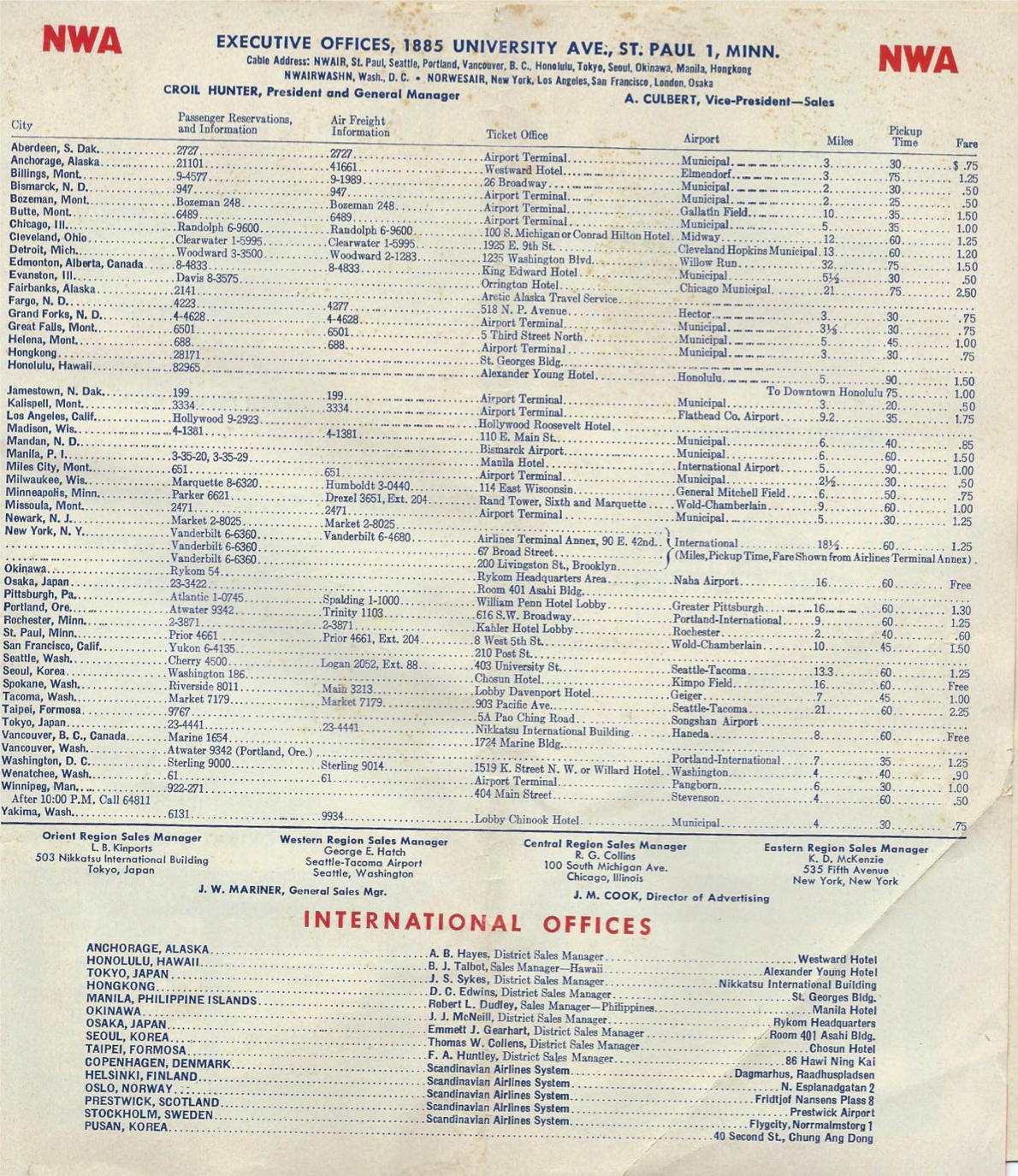

In 1971, Cathay Pacific bought twelve long-range Boeing 707 jets from Northwest Airlines (as that carrier rolled out 747 operations), and this allowed expansion to Sydney in 1973.

But it would take until 1980 for Cathay to be permitted to reach London, 1983 to cross the Pacific and make landfall at Vancouver, and 1986 to achieve service at San Francisco. And that will be a story for another day...