Korean Air - Emergence of a Global Carrier - 1976

/First Steps Across the North Pacific

South Korea’s reconstruction after the ravages of World War II and the Korean War took decades, and while there were two launches of an official state airline (KNA in 1947 and the first version of KAL in 1962) the networks they built were fleeting and unprofitable, reaching Japan and Hong Kong only inconsistently until 1965 and 1967. Foreign traffic to Korea in the 1960s was carried primarily by Northwest and Pan Am, Japan Air Lines and Cathay Pacific.

In 1969, the government in Seoul handed the assets of Korean Air to the Hanjin Group. This chaebol was already well-established in ocean shipping and road transportation, owned a company that built hotels, ports, and roads, and owned another company that ran fuel and ground-handling operations at all the country’s airports. Hanjin’s management had big plans for their airline, as well as the talent and funding to execute them.

Hanjin quickly added high-capacity YS-11 turboprops and Boeing 720 four-engine jets to the small Korean Air fleet of Fokker F-27 commuter propliners and DC-9-30 short-range jets. They also grew their route network south to Vietnam and Thailand, and increased links to Japan.

In 1971, KAL added the long-range Boeing 707-320, first in its cargo version (as Korea's manufacturing boom had moved into full gear) and then the passenger version. They started cargo flights to Los Angeles in April 1971, and passenger flights in April 1972, routing via Tokyo and Honolulu.

The initial service ran twice a week, but demand for both seats and cargo space was so strong that it had gone to daily frequency by the next year. Still the demand could not be met, so Hanjin put in orders for the Queen of the Skies, Boeing's 747, and put them on the Los Angeles run in 1973.

Challenge to Asia's Traditional Hub Network

Those early-build 747s, and the 707-320s and Douglas DC-8-63s in the KAL fleet in the early 1970s were state-of-the-art aircraft for their time, but their range was insufficient for long-range services to Asia. Flights to and from Europe had to go all the way around China and the Soviet Union, so those services usually made two or more stops; somewhere in Southeast Asia and somewhere in the Middle East. Flights to California from the Southern Pacific had to stop at Honolulu for fuel, and across the North Pacific, only Tokyo's location was close enough to allow for nonstops to California. Even then, Northwest and Pan Am needed to use Anchorage, Alaska as a fuel stop on their runs from Chicago and New York City to Tokyo.

Another reason why Tokyo was Northeast Asia's dominant hub was the treaty obligation Japan had not just to the United States, but all the World War II Allies, to allow those countries' airlines to use Japan not just as a stop-over point on their way somewhere else, but also to be able to sell tickets from Japan to "somewhere else". For Korean Air, this meant they could sell not just Seoul-Tokyo, Seoul-Honolulu, and Seoul-Los Angeles, but also Tokyo-Honolulu and Tokyo-Los Angeles: this ensured full flights and steady profits.

The catch to the Tokyo stopover, though, was that flights coming in from one direction had to be balanced by flights going onward in the same direction. This wasn't a problem for Northwest, who could run aircraft in from Seattle, Chicago, California, and Hawaii and then out to a similar number of destinations on the other side of Japan. But it did limit Korean Air, who only had Seoul as a major outbound origin point of Transpacific traffic.

And this was a problem for fast-growing Korean Air, who really wanted to increase frequency to California, and also to open up service to Europe. The only solution was to bypass the Tokyo hub.

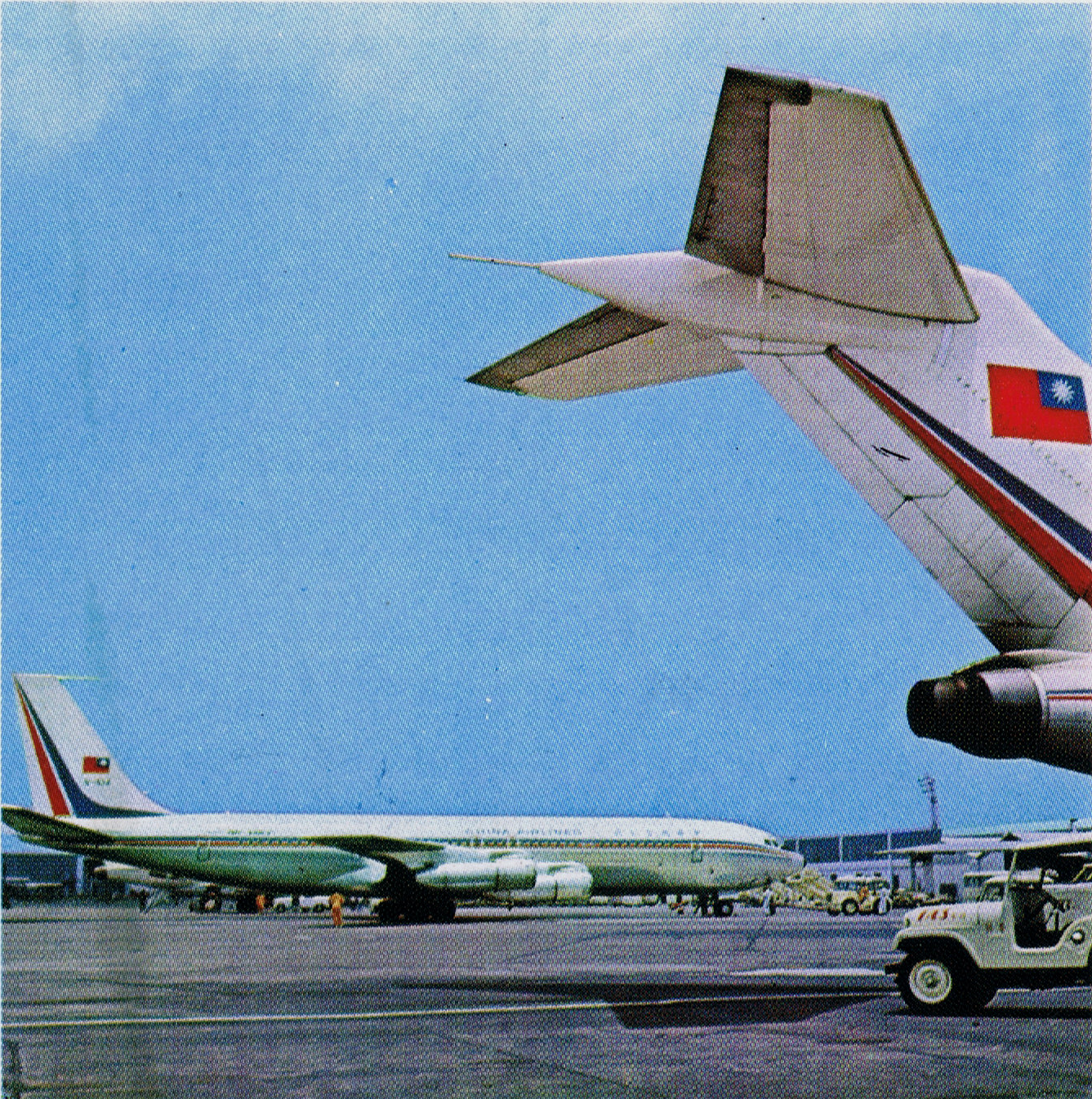

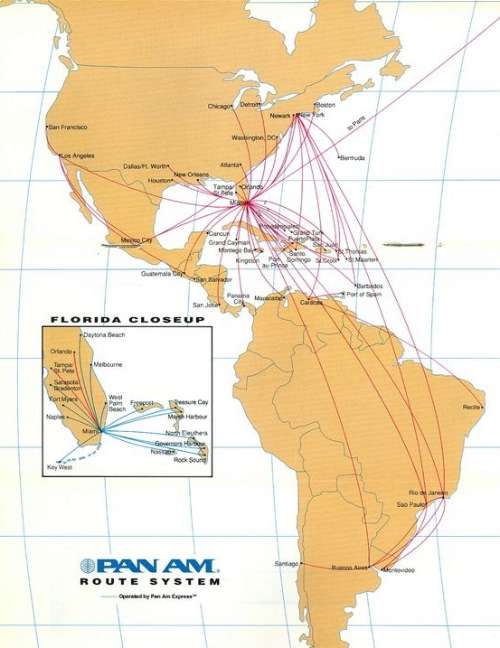

Click to expand image.

So for California, in addition to the Seoul-Tokyo-Honolulu-LAX flight, Korean Air added a 747 nonstop Seoul-Honolulu which also continued on to LAX. By April 1976, this allowed KAL to serve Los Angeles with passenger flights 10 times per week.

And for Europe, in March 1975 KAL started a Seoul-Anchorage-Paris passenger run twice per week with 707 equipment. This was the critical move: while Anchorage wasn't itself a passenger traffic source, it was on the North American continent and on the Great Circle Route not just to Los Angeles but even New York City. Also notice on the route map above that KAL was already using Anchorage as an enroute stop for cargo service to California.

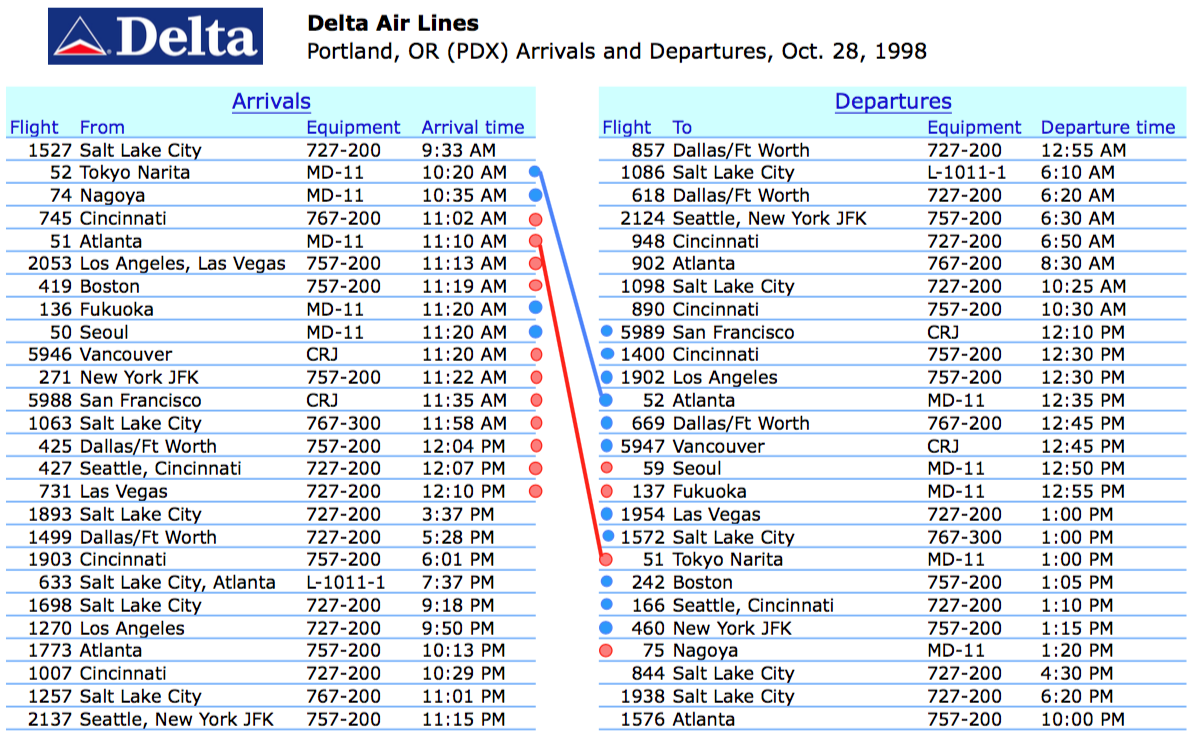

International services on Korean Air from Seoul in the April 1976 timetable.

With the April 1976 timetable, KAL introduced new Douglas DC-10-30 widebody jets for long-range service. And KAL by that point also had on order new variants of the Boeing 747: the ultra-long range 747SP, and the improved 747-200.

These would allow service to New York to begin in March 1979 via Alaska, and at long last, nonstop service from Seoul to Los Angeles in September 1979. Korean Air had the equipment, personnel, and experience to fully-exploit the North Pacific routing and establish a true alternative to the Tokyo hub for North American traffic.

KAL used those DC-10s and 747s to dramatically open new service to the Middle East as well, starting Bangkok-Bahrain flights shortly after this timetable published, and ultimately seven destinations there by the early 1980s, as the Hanjin Group scored airport construction contracts across the region, and needed Korean labor to build them.

Here's how far KAL had reached by early 1981.

By the mid-1990s, Korean Air had also covered the Americas, with passenger flights to 11 destinations in the USA, Canada, and even Brazil!

Underscoring the importance of the North Pacific routing, Korean Air reached an agreement in 2017 with Delta Air Lines (successor to Northwest) to create a joint-venture partnership that will allow Delta to shut down its intra-Asia mini hub at Tokyo.

Also see...

Our family-travel airport guide to Seoul-Incheon

What Your Kids Should Eat in Seoul