United - acquisition of Pan Am's Pacific Division 1986

/Composite image; Pan Am DC-10 by Aero Icarus via Flickr, CC 2.0 license, and United DC-10 by Alain Durand, GNU 1.2 license

A tale of two airlines

By late 1984, it was clear that Pan Am’s strategic blunders were not going to be fixed by a recovering economy: it had paid far too high a price to acquire Miami-based National Airlines for domestic routes that did nothing to feed its New York-JFK hub, and couldn’t even effectively feed its South American services. The airline was saddled with first-generation, fuel-hog jumbo 747s and 747SPs it couldn’t fill except at highly discounted fares, against high fuel prices and interest rates.

Delta, Northwest, and American were now competitors across the Atlantic, and flying from their respective fortress hubs where they could collect and re-route passengers much more effectively than Pan Am could through New York. On its historic Latin American services, Eastern picked up the former Braniff routes when Pan Am could neither pay nor get government approval, and had swiftly integrated them into its massive Miami hub.

On the Pacific side, Northwest had already exceeded Pan Am’s lift into Tokyo; United had been given flights to Tokyo and Hong Kong; and Japan Air Lines, Korean Air, and Singapore Airlines were not only adding capacity to the USA, but doing so with a level of service and seating comfort that Pan Am had not invested in.

Image by Roger W via Flickr, CC 2.0 license

Pan Am was bleeding cash and had sold off its InterContinental Hotels chain and its iconic Manhattan office tower, but its debt obligations were still daunting. And a ground-services strike in early 1985 consumed nearly all the cash Pan Am had on hand. The situation at their New York headquarters was desperate.

Meanwhile, in Chicago, United Airlines’ top management was full of confidence: revenue for the largely-domestic carrier was steadily climbing, as was profitability. They had successfully introduced a fleet of new, fuel-efficient Boeing 767 widebody jets and this was allowing them to phase out old-generation DC-8s and improve their margins at the same time.

Profits from operations meant United had a more-open wallet by lenders, and Chairman Richard Ferris was pulling together a plan to employ that leverage to create a vertically-integrated travel company: using United’s reservations system Apollo, and the Western International Hotel brand they already owned (now called Westin), he acquired more hotels and the Hertz rental car chain – with the goal of owning every step of a traveler’s journey. We would call it a “big data” strategy today – Apollo was one of the biggest computer networks on the planet in the 1980s and had strong penetration in the nation’s travel agencies, and Ferris’ theory was that a one-stop shop would allow United to win a higher percentage of big corporate travel contracts because Apollo could help those companies better track and control their travel expenses.

The corporate name was supposed to be a fusion of "allegiant" and "aegis", and what either of those two concepts had to do with travel no one really understood...

1983 route map - note the co-promotion of Westin Hotels

Yet United’s management still felt vulnerable: while it was the largest U.S. domestic carrier, it had nearly no high-margin/high-prestige international service, outside of its two Asian routes. The U.S. government had still not approved any of United’s other requests for Pacific and Atlantic routes, and so it found itself feeding its competitors, especially at its San Francisco and Los Angeles hubs.

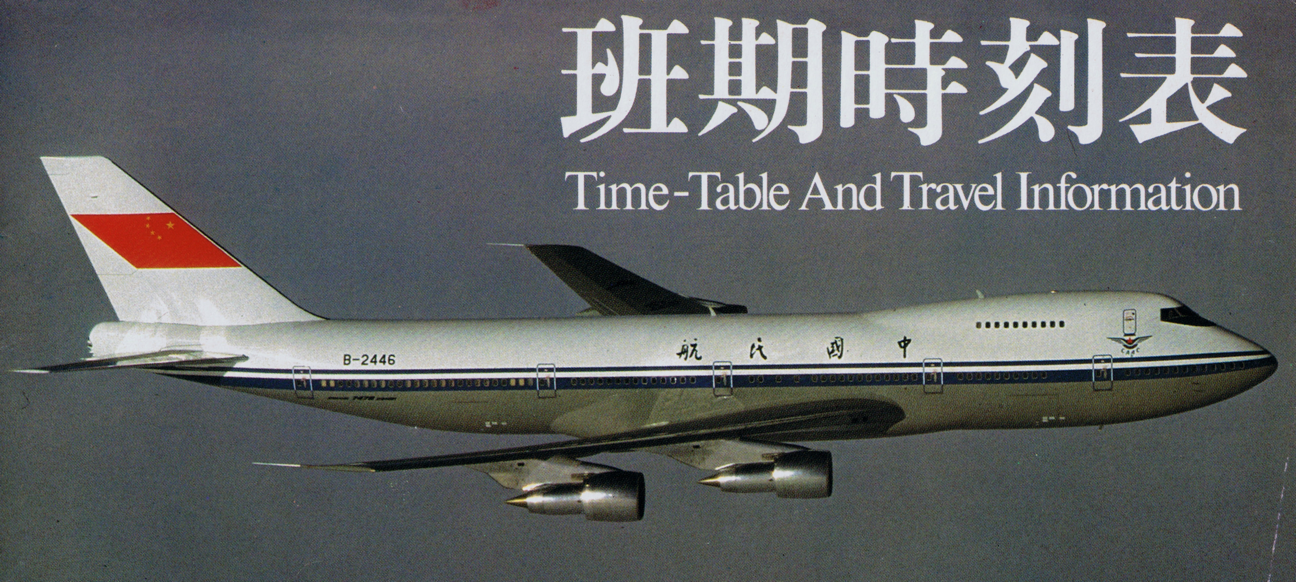

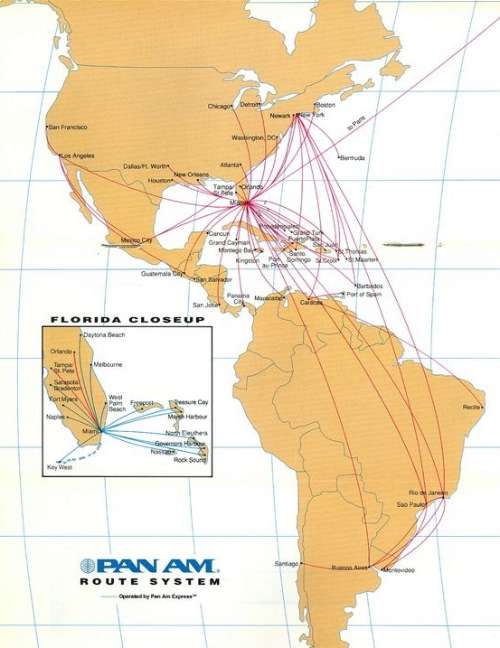

Pan Am's Pacific system in 1982-1984

Let’s make a deal

So when Ed Acker of Pan Am called Ferris in February 1985, both sides were hungry for a deal. Ferris, in fact, had been proposing an asset purchase for three years. Negotiations went on in secret for a month; neither sides’ creditors or investors were aware until the deal was announced at a joint press conference in April. Wall Street “was taken by surprise” but analysts quickly said both airlines would benefit.

For about $750 million in cash, United would pick up all of Pan Am’s routes to East Asia and the South Pacific, plus 2,700 staff and 18 aircraft (11 Boeing 747SPs, 6 Lockheed L1011-500s, and one McDonnell Douglas DC-10-30 – though United would give Pan Am 5 747-100s). Given that Pan Am was grossing about $770 million and making about $55 million in profit off its Pacific division, it’s clear that United made a very good deal.

Pan Am bought some time with the asset sale – on the positive side, they started to bring on Airbus A300s for Caribbean and transcontinental flights, and Airbus A310s for lower-traffic European routes, made a more-serious attempt to build domestic connecting traffic into New York JFK, and started a Washington-New York-Boston air shuttle. On the negative side, they were still carrying too much debt, the fleet was still 747-heavy, and competitors were moving much faster to claim market share. Pan Am would end up selling off its crown jewel of flights and landing rights to London’s Heathrow Airport to United in 1990, but still couldn’t cut its way to viability. After the Lockerbie bombing of a Pan Am 747, the airline attempted to form an alliance with Delta Airlines, but that deal unraveled and the carrier shut down entirely in December 1991.

Pan Am's final route map.

United’s management was feeling great about the Pacific deal in April 1985 – but they’d left their pilots without a contract for two years. So in May 1985, the pilots and then the flight attendants went on strike for a month, shutting the carrier down nearly completely. United’s agreement to end the strike did not resolve the issues, but rather created a two-tier contract where newly-hired pilots would never see the wages or benefits that older pilots had earned. Instead of easing labor-management relations, the work environment only grew more tense. The pilots’ union considered Ferris an enemy.

Over the next two years, Wall Street would also find complaints with Ferris’ performance, as his vertical-integration strategy failed to deliver superior returns – leading the pilots’ union to ally with investment fund managers and attempt a takeover of the whole company. Soon, Hertz and the hotels would be sold off, and Ferris would be out of a job.

The new system

The pilots’ strike was a drain on cash and management attention, leading to delays in closing the deal. However, by February 1986 the Pan Am aircraft, gates, staffing, landing rights, and contracts had all been signed over, and after quick application of decals to the fleet, on February 11 United began operation on its new division.

Photo by FotoNoir via Flickr, CC 2.0 license

Photo by FotoNoir via Flickr, CC 2.0 license

United would continue to suffer labor pains and incur debt issues in the 1990s despite continued growth and further asset buys from Pan Am, but for this story, the Pacific Division became a point of pride for the company and marked its ascendance to becoming a true global carrier. Through reorganizations, the crisis after 9/11, and the merger with Continental, these routes only grew in importance to the carrier.

March 2017 routes from United's Hemispheres Magazine

Today’s United Pacific network still carries the fingerprints of Pan Am’s services, but with frequencies and capabilities that Pan Am could never dream of. Some of those new pioneering services will be discussed in future posts in this thread...

Also see:

http://articles.latimes.com/1985-04-23/news/mn-11435_1_united-airlines

http://archive.fortune.com/magazines/fortune/fortune_archive/1987/07/06/69232/index.htm

https://namedropping.wordpress.com/2010/11/13/the-allegis-disaster-and-the-juliet-syndrome/

http://www.slate.com/articles/arts/the_motley_fool/1997/07/you_name_it.html

and other weninchina resources - - -

Our Transpacific Flying folder on Pinterest

Our Tokyo-Narita airport guide