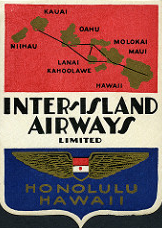

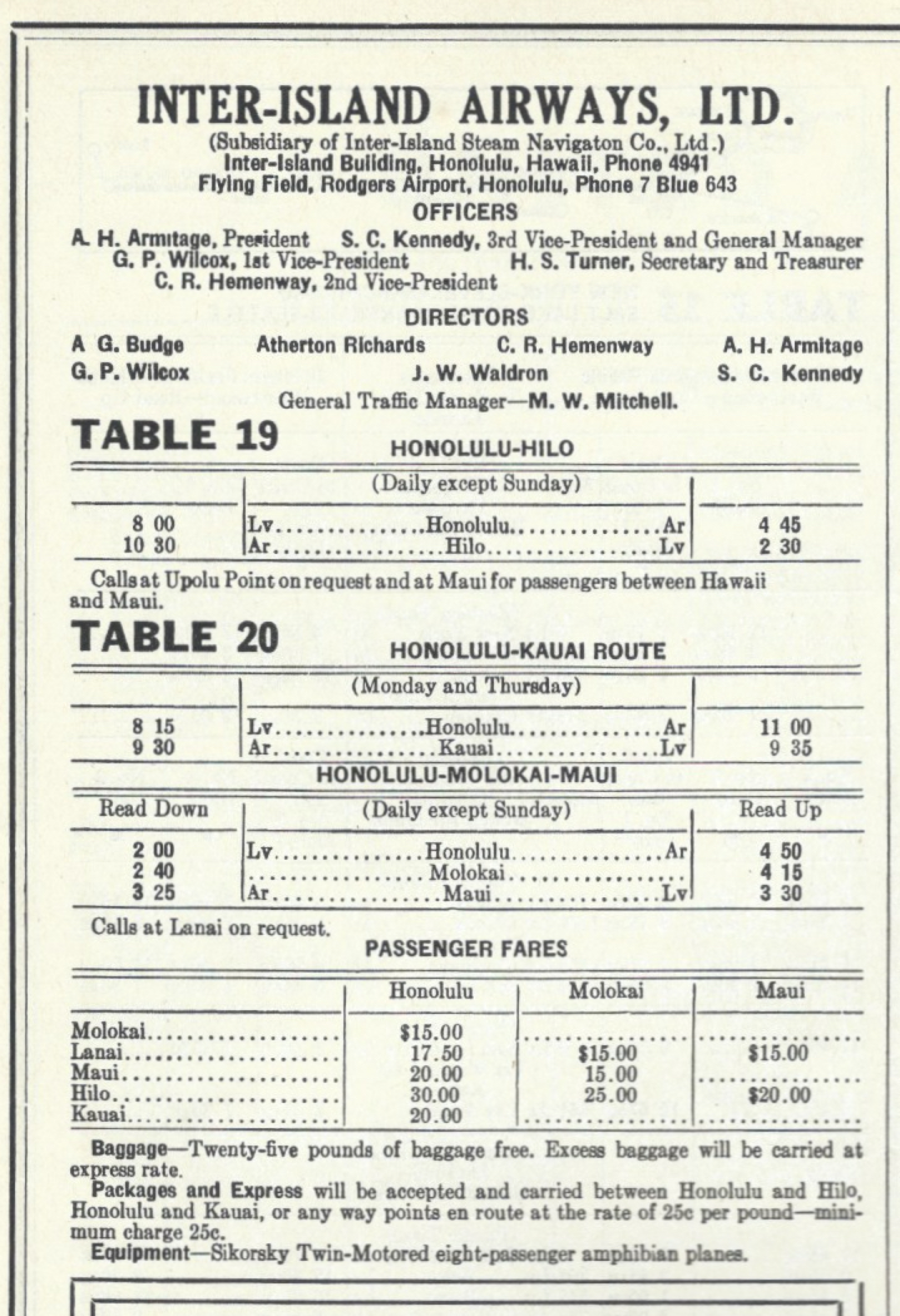

Inter-Island Airways - June 1931

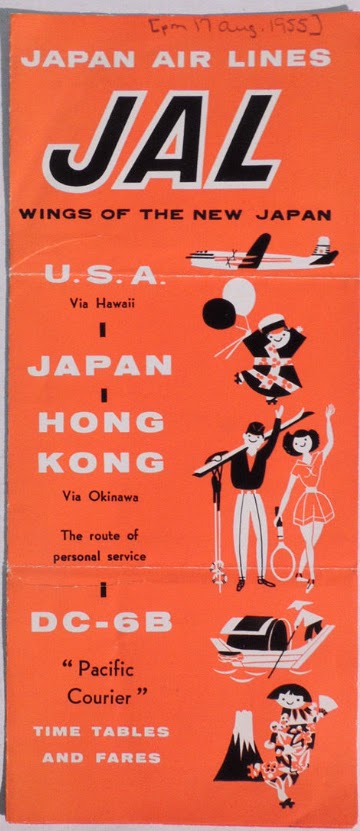

/Well before Juan Trippe had the business audacity and deep connections with the US government to build a network of island terminals to start Pan American’s famous China Clipper service from San Francisco – Honolulu – Manila – Hong Kong, there was a realization in the territory of Hawaii that air travel would provide the crucial speed and hopefully safety to tie the island chain together: ships of the era needed a day and a half to transit between the Big Island and Oahu amid strong wind and changeable weather.

Several attempts were made in the early 1920s to begin commercial service, but the craft were unreliable and could not carry an economical load. It took the Inter-Island Steamship Company, one of the two big lines serving the Islands, to put serious capital and talented people behind figuring out how to make flying work.

The Army and Navy were at odds with each other about where and what kinds of airfields to build and where across the territory, so the Inter-Island team decided to go with an aircraft that could land on water as well as paved runways: the 8-passenger Sikorsky S-38 amphibian, already in use with Pan American in the Caribbean, Northwest on the St. Paul-Duluth run, and Canadian operators.

The airline’s first official passenger flight was on November 11, 1929 on the Oahu-Maui-Hilo trunk line – not long after the stock market crash and beginning of the Depression. The steamship company was able to absorb operating losses from the airline while it built operational experience and finally earned its essential US Mail contract in 1934. Recovery in tourism – especially with Pan Am’s Clipper service cutting four days’ travel time from the mainland - plus the military buildup in the Islands and guaranteed mail income led to profitability and the acquisition of larger and more capable Sikorsky S-43 flying boats in 1935.

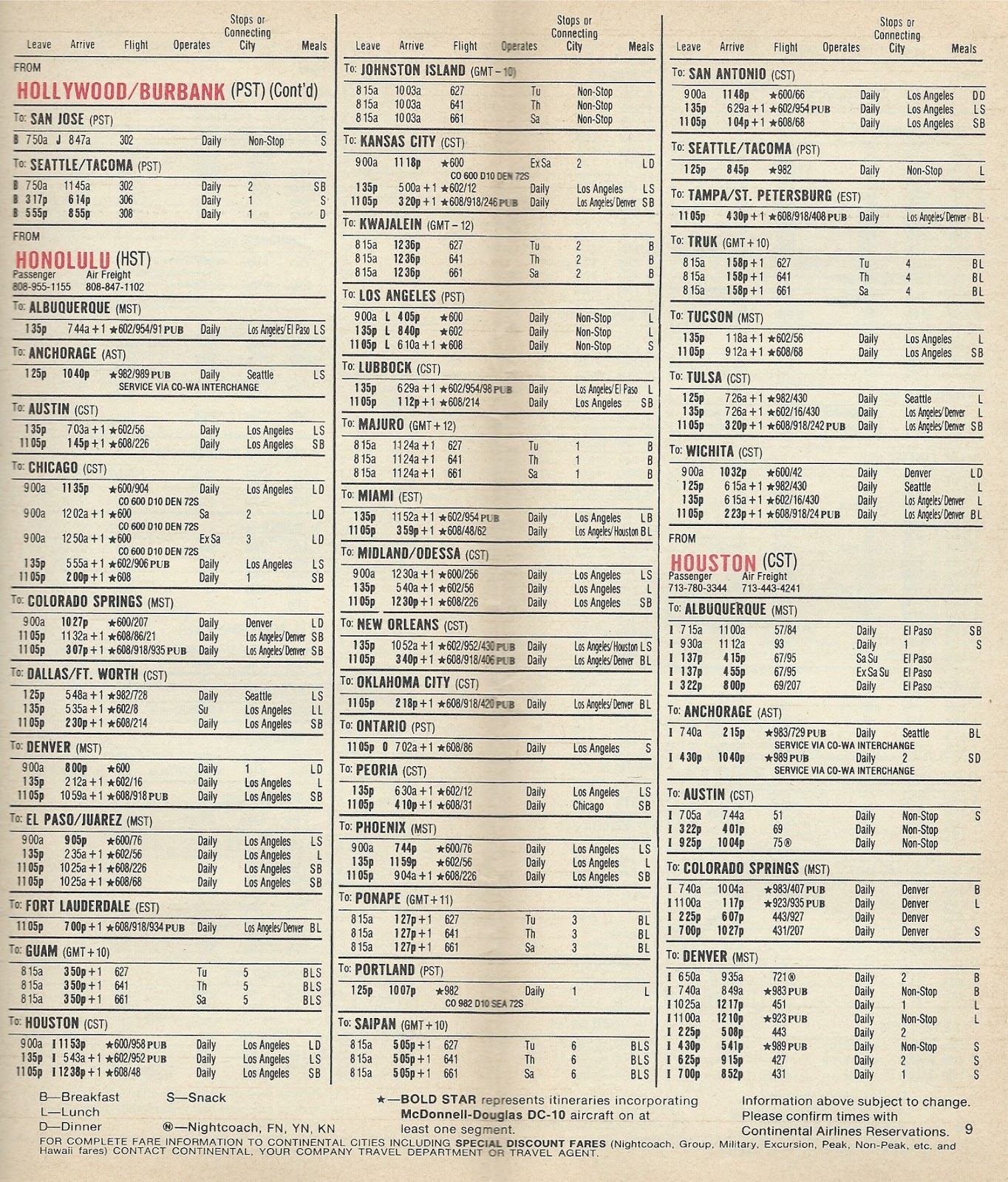

From my own collection, scan of the Official Airline Guide

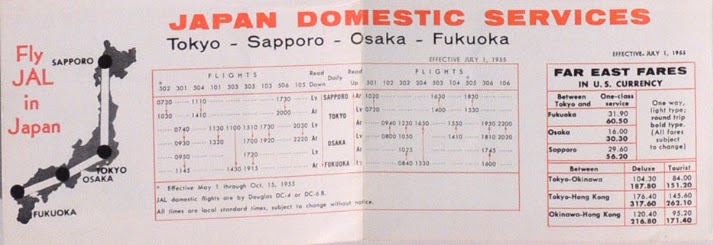

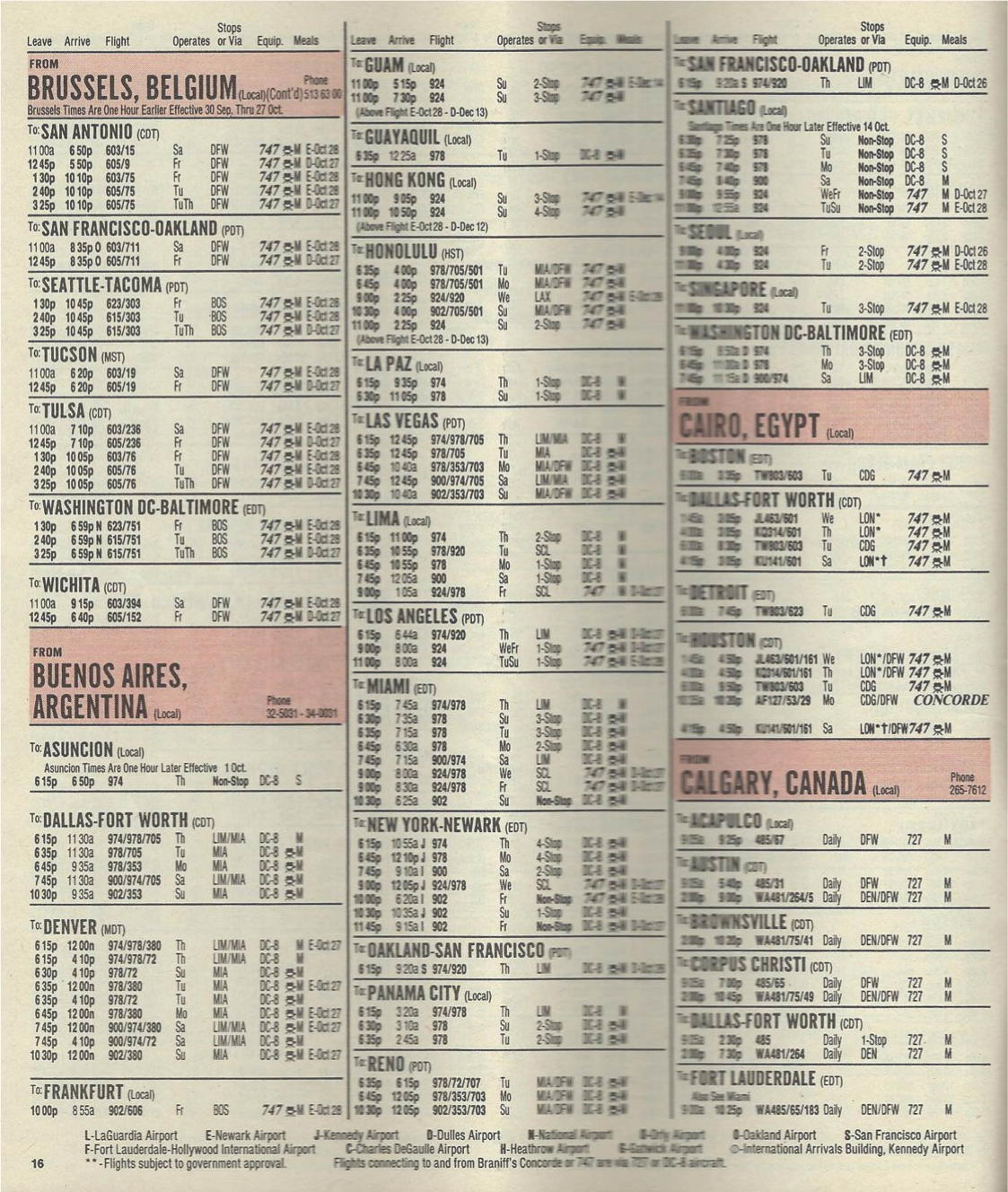

In this June 1931 timetable we can see the entire system being covered with just two aircraft:

- A morning run daily from Honolulu out to Hilo, where the aircraft would sit for four hours. The return flight would land in Oahu at 4:45pm.

- A morning run twice a week from Honolulu west to Kauai, turning around and getting back to Oahu before lunch. At 2 pm, the craft would handle the Honolulu- Molokai- Maui run, returning before 5 pm.

This schedule gave plenty of operational flexibility and, importantly, all-daylight operations. Navigational radio beacons were not in place at the time, and these aircraft could not fly above tropical weather. Also too, landing in ocean waves and taxiing reef-protected harbors were not (and are still not) wise to do at night.

After World War II, the company (now named Hawaiian Airlines) was flying DC-3 landplanes and graduated to Convair 340s in the 1950s, and turboprops and DC-9 jets in the 1960s. Finally in the mid-1980s, Hawaiian entered the Hawaii-California market.

Hawaiian Air A330 at Honolulu

From the mid-2000s, Hawaiian has become the largest inter-Island carrier as well as the leading airline to the Mainland US. They now also fly to other South Pacific islands, Australia and New Zealand, as well as Japan, Korea, and China - the realization of Pan Am's 1930s vision of linking the entire Pacific together via Honolulu.

Excellent resources to learn more about Hawaii's aviation history:

http://aviation.hawaii.gov/pioneer-airlines/inter-island-airwayshawaiian-airlines/

https://evols.library.manoa.hawaii.edu/bitstream/10524/623/2/JL37203.pdf

Also see: