Delta Air Lines' Asian mini-hub in Portland

/Image by JKruggel via Wikimedia Commons, CC 3.0 license

A clever improvisation

In the second half of the 1980s, management at Delta Air Lines had come to the conclusion that the carrier had to either grow significantly or else be at risk of a hostile takeover. Growth it had to be, and they used the strength of their Atlanta hub to open up new routes across the Atlantic, feeder services throughout the Southeast, and out to nearly every major city in the U.S., including Hawaii.

But that wasn’t going to be enough: Delta had strength on the East Coast and across the South, but only tendrils to the West. A merger opportunity presented itself with Western Airlines, headquartered in Los Angeles, with a smartly-run mountain-states hub in Salt Lake City, and strong coverage up and down the West Coast, Hawaii, and Mexico. In April 1987 the carriers combined. Delta, however, knew to secure their position as a “top 3” US carrier, they would have to grow even further west…

Ambitions for Asia, but with one big problem

By this time United had acquired Pan Am’s Pacific system, and Northwest Orient was continuing to open up new services (and was on the hunt for acquiring another carrier themselves). Delta was not going to be able to buy their way into a large network like they did with Western, so they were going to have to build it from scratch.

Even in the 1980s, Delta’s Atlanta hub was the largest operation of its sort, easily capable of filling flights to Frankfurt, Paris, and London as the Sunbelt’s industry continued to grow and Florida continued to add attractions and beach developments. Opening a route to Tokyo would certainly be successful – and as Delta would be the official airline for the 1996 Olympics, they had to have an Asian connection to the city.

Photo by Aero Icarus via Wikimedia Commons, CC 2.0 license

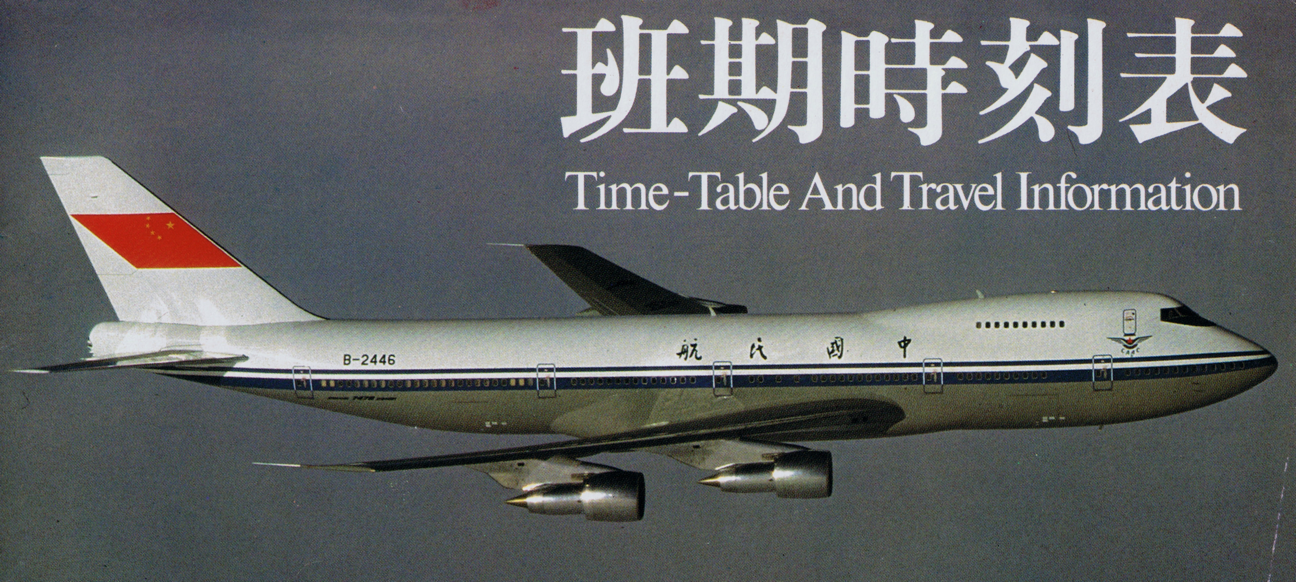

But – the flagship of Delta’s fleet, the three-engined widebody Lockheed L-1011 Tristar, simply did not have the range to get to Asia from Atlanta. Even its high-performance model, the L-1011-500, was best suited for runs to Germany or Hawaii – not nearly far enough. And Lockheed wasn’t going to make a better TriStar for Delta, because they had just quit the civilian airliner market.

So Delta ordered the new McDonnell Douglas MD-11 long-range widebody (itself the ultimate derivative of the venerable DC-10), but those birds wouldn’t start to be available until 1990. Delta needed a solution to open up Transpacific flights, quickly, before American or Continental moved into the market in earnest.

Photo by Dean Morley via Flickr, CC 2.0 license

Options from the West

Not only was Delta constrained by the capabilities of its fleet, it was also constrained by the location of its new Western Airlines assets:

- Los Angeles had ideal local demand for Transpacific service, and could use the many Delta/Western flights to feed connecting traffic. And the L-1011-500 might be just able to make Tokyo or Seoul (perhaps with a brief refueling stop in Alaska.) But there were no government-issued route authorities available to Japan or Korea in the late 1980s: United and Northwest had already claimed all the new slots and were using 747 equipment that could fly them nonstop.

- Salt Lake City, while smaller, nevertheless had an excellent ability to corral connecting traffic. But its high elevation meant the TriStar had no chance of reaching Asia.

- Seattle was a major terminal point for the combined carrier, but Northwest and United dominated all the possible routes westward.

- Portland? United had just given up its once-per-week flight from Portland to Tokyo-Narita in favor of beefing up its Seattle service, so there was no westward competition… and a TriStar leaving PDX would have enough range to make Japan or Korea.

PDX marks the spot

Portland in the late 1980s was a city in transition, moving from its regional economy and industrial and agricultural base to its globally-connected future of arts and crafts, technology, music and sports gear, and cuisine. It wasn’t yet the “spirit of the ‘90s” boomtown but it was growing – and being in the Pacific Northwest, of course it had a significant Asian population and important business ties to Japan, Korea, and China.

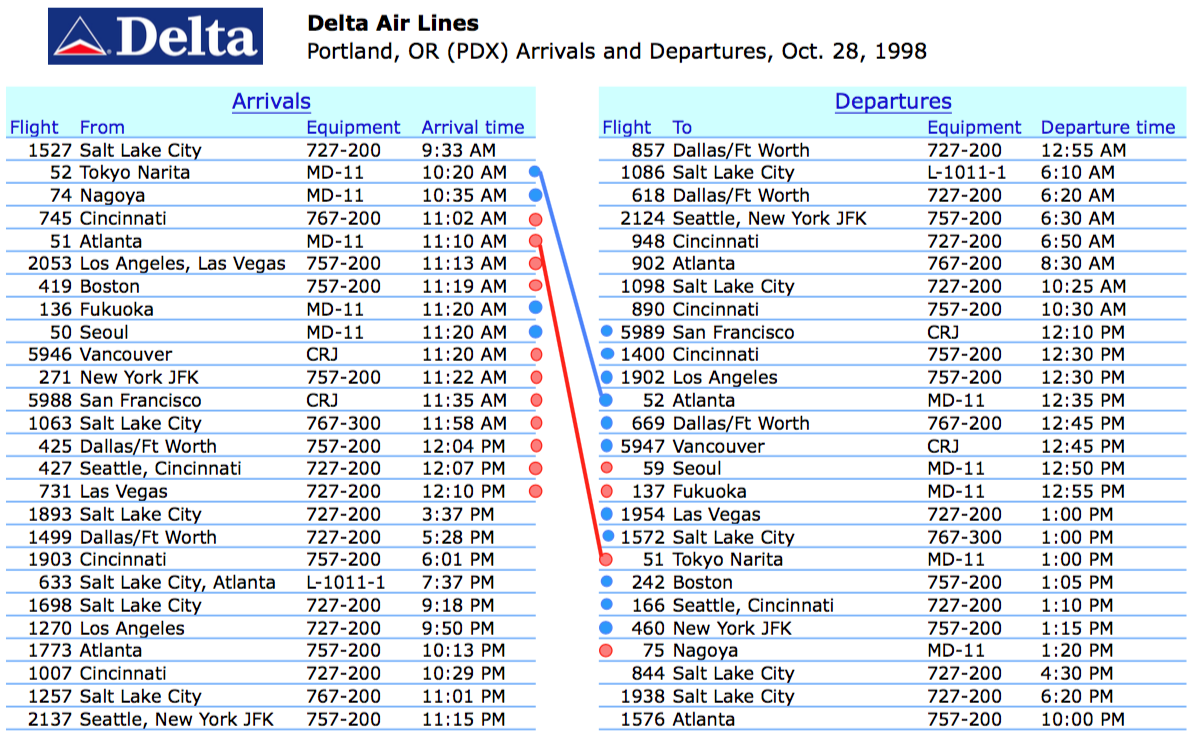

The combined Delta and Western route network that served Portland also happened to have ideally-timed connecting flights from all the carrier’s hubs, as well as San Francisco, Seattle, Vancouver, and Anchorage.

Even before the merger with Western was consummated in April, on March 2, 1987 Delta started 5-per-week nonstops from Portland to Tokyo-Narita with the L-1011-500, with the flight originating in Atlanta.

That seemed to work

Delta was immediately pleased with the small, elegant “scissor hub” operation at PDX: they occupied a handful of gates at the end of Concourse D and Customs processing for inbound passengers was literally one floor below. Travelers could go through immigration and be back on their airplane bound for hubs at Atlanta, Cincinnati, Dallas, or Salt Lake in far less time than it would have taken to handle them at Los Angeles or San Francisco. As predicted, the route was successful.

Delta had no ambition to turn Portland into a massive hub; Salt Lake City was already built up and handled intra-western connections at a low cost, plus Portland was too far north to capture California-to-Midwest/East Coast traffic. All it needed to do was pipeline Asian passengers and freight onward to Delta’s primary hubs, at a modest investment.

A second Transpacific route was opened in December 1987, to Seoul, also with the TriStar. At first the Tokyo flight simply continued on to Korea, but was made a nonstop in its own right in 1988. With two routes, the timing of arrivals and departures at PDX was re-tuned so that the Seoul run came in and out almost wingtip-to-wingtip with the Tokyo flight.

Encouraged by success to Korea, Delta extended the route from Seoul to Taipei in July 1988, and from Taipei to Bangkok in December 1989, taking advantage of unused route authorities. Finally in 1991, they launched a Portland-Nagoya, Japan nonstop.

The disappointing MD-11 (was good for Portland)

Delta put its new MD-11s on the Asian routes as soon as they were delivered, and by 1993 the TriStars were on their way out of the Pacific (though it took them until 2001 to finally be retired by Delta.) The extra freight capacity on the new aircraft was appreciated and profitable, and the relatively-shorter hops across the Pacific from Portland were ideal for training the crews who would take the MD-11 on the anticipated super-long-range flights.

Except the MD-11 never met its promised performance. Too heavy and underpowered when fully loaded to attain the range of a new 747-400 despite its smaller capacity, nearly every airline who bought it immediately started looking for a replacement. If Delta wanted to fly nonstop from Atlanta to Tokyo, they’d have to do so with severe constraints on how heavy they could load it.

Which meant Delta would not be dismantling Portland right away, despite other challenges that airline was facing in the 1990s:

- Retreat from its large base at Chicago O’Hare in the early 1990s

- Acquiring many European routes (including a mini-hub at Frankfurt, Germany) as well as the Boston-New York-Washington shuttle, from defunct Pan Am – the Frankfurt hub would close in 1997

- A fumbled attempt to build a low-cost “airline within an airline”, Delta Express, to handle tourist routes into Florida from Eastern and Midwestern cities.

- Big construction projects at the Cincinnati and Dallas/Ft. Worth hubs

- Southwest Airlines expanding in force along the West Coast and at Salt Lake City, depressing yields throughout the former Western Airlines territory

- Actually getting authorities and landing slots to run Los Angeles – Tokyo, as well as Los Angeles – (Anchorage fuel stop) – Hong Kong

Delta was getting to be a very big airline and was facing big-organization challenges, but they did appreciate that Portland was still an efficient and passenger-pleasing element of their Pacific strategy. So the carrier invested modestly to build additional gates and a premium lounge, and even put their MD-11 maintenance base there. From a modest 4-gate beginning, Delta was operating 20 gates at PDX by 1998.

With Delta’s attention focused on Europe in the mid-90s, the links to Anchorage, Bangkok, and Taipei were cut, but a flight to New York was added. In 1998 they added Boston and Las Vegas domestic service, plus a new route to Fukuoka, Japan, and announced service to Osaka, as well.

MD-11 landing at Narita Airport. Photo by saku_y via Flickr, CC 2.0 license

And they were confident enough in their Japanese traffic to start Atlanta-Tokyo nonstops with the MD-11, even though it would have to fly with weight restrictions. That meant Atlanta had double-daily service to Tokyo in Summer 1998; one nonstop and one flight via Portland.

(Don’t just blame it on) the Asian economic crisis or September 11

Despite Southeast Asia’s severe recession, originally caused by exchange rate manipulation in Thailand in 1997, Delta was still doing good passenger and freight business well into 1998 – and was confident enough in their own forecasts to add extra flights as described above.

But by Fall 1998 the crisis had moved well beyond Southeast Asia and pushed South Korea, Japan, China and Hong Kong into economic free-fall: outbound tourism evaporated and imports of US foods, energy, and manufactured goods collapsed.

In response, Delta cut its Osaka route before it even started, and stopped running the one-stop service from Atlanta to Tokyo – instead, shifting the one-stop flight to their second-largest hub, Cincinnati.

Those cuts weren’t sufficient to keep Transpacific service viable, however, as the “dot-com crash” in the USA started to gather momentum. In April 1999, Delta had to drop its Portland-Seoul and Portland-Fukuoka flights, leaving it with just Tokyo and Nagoya nonstops. Domestic service to technology center Boston was also dropped then.

The loss of technology jobs in Portland, coupled with the hit to freight volume as Japanese consumers stopped buying expensive (to them) Oregon blueberries, Washington apples, and Pacific-coast salmon, meant that PDX itself could no longer contribute strong local traffic to Asian flights.

Even by 1998, Delta had stopped running a full schedule of flights between Portland and Los Angeles, keeping only one round-trip between the cities; Southwest and Alaska Airlines had captured much of the volume up and down the West Coast by then. Delta was not operating LAX as a hub at this time and essentially abandoned many of the shorter-range legacy Western Airlines routes it picked up in the merger. Likewise, Delta had downgraded the Portland-San Francisco and Portland-Vancouver services from a full-size 727 to the cramped 50-seat Canadair Regional Jet. This meant there was less feed available from the coastal cities to connect onto the Asian flights.

While the concept of airline alliances was still in its early stage in the late 1990s, Delta had struck up an arrangement with Korean Air for joint sales on that carrier’s Seoul-Chicago-Atlanta and Seoul-New York-Washington services, cushioning the impact on Delta’s network of dropping its flight to Korea. But Delta did not have any partners to connect with at Tokyo-Narita (a problem that never was solved even after the merger with Northwest), and this too made it more difficult to sell seats on the run to Portland.

Another indirect strike against the Portland operation was Delta’s introduction in late 1999 of its replacement for the MD-11: the Boeing 777-200. Initially Delta put these aircraft on services to Europe, but its capability to fly Atlanta-Tokyo nonstop with a full load meant the clock would be running out for the Portland scissor hub.

MD-11 maintenance was relocated to Atlanta, and in September 2000 the announcement was made that the PDX flights to Nagoya and Tokyo would be ending with the April 1, 2001 schedule update, and the city would just be a “spoke” for its hubs at Atlanta, Salt Lake City, Cincinnati, and Dallas/Ft. Worth. So even before 9/11 and its devastating impact on the world’s air travel, Portland was already off the international grid.

Back on the map, for now

Photo by Cory Barnes via Flickr, CC 2.0 license

After the world’s economy had shaken off the Asian currency crisis and post-9/11 shock, freight and passenger demand started to pick up again over the North Pacific. But it would be Northwest Airlines who would re-start service from Portland to Tokyo, where that airline had a mini-hub at Narita. NWA used its new-generation A330, starting in April 2004. This service has continued through the present day, although when Northwest and Delta merged, Delta assigned one of their slightly smaller, long-range 767-300 aircraft to the route.

However, with Delta starting to dismantle its Tokyo-Narita operation, and adding significant Transpacific capacity out of Seattle, the Portland service is once again at risk. Will the route remain viable in Delta’s eyes on the basis of local passenger and cargo demand? Will Delta’s joint-venture partner Korean Air start service to Seoul, giving Delta rationale to drop the Tokyo flight? Or will one of the Japanese carriers decide to move onto the route?

Photo by Andrew Nash via Flickr, CC 2.0 license