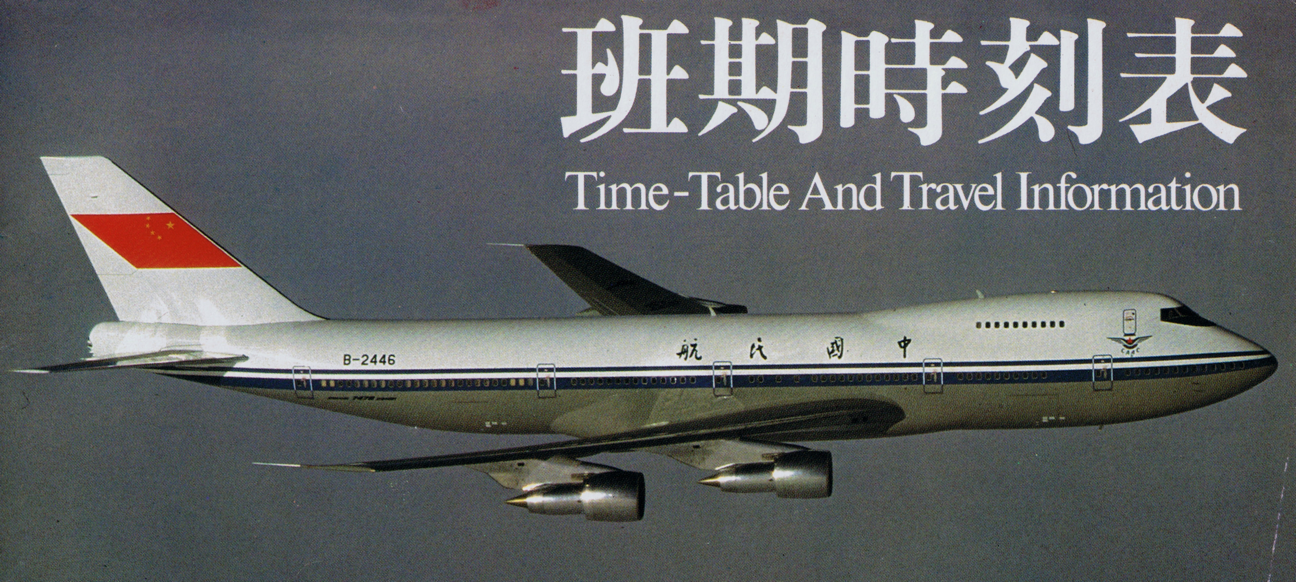

Northwest Orient Airlines’ 747 inaugural service - 1970

/The Queen of the Skies was made for routes like these

December 2017 marks the end of scheduled 747 service for Delta Air Lines, and with the final aircraft in its fleet making a farewell tour, it’s appropriate to take a look back at how merger partner Northwest Airlines began service with this type back in 1970.

Northwest Orient, as they were styling themselves, had placed orders for ten of the all-new Boeing 747-100 in 1966, not long after Pan Am had launched the type, and they started receiving their jets only a few months after Pan Am, as well. All ten were delivered in 1970-71, and Northwest topped up its order with five more 747-100B longer-range variants to be delivered in 1971.

By 1980 Northwest had started to swap in the newer, more-capable 747-200 (as well as a handful of all-cargo models), and would later go on to be the launch customer for the extended 747-400. The -400s would pass on to Delta when the companies merged, but the remaining -200s were quickly disposed of, as well as the all-cargo subfleet.

Northwest’s system map in Spring 1970 showed a mix of local-service flights across the upper Midwest and Mountain states, with trunkline services among many major Northeast and Great Lakes cities, plus new lines to Florida and California, and of course long-haul service across the Pacific. Minneapolis and Seattle were their main domestic bases, but they also had a significant presence at Chicago, and had even scored Chicago-Hawaii nonstop authority (in competition with United.) NWA was using several types of Boeing 707 and 727, and a dwindling number of Lockheed Electra prop-jets to fly the system.

Photo by Ken Fielding via Wikimedia Commons, CC 3.0 license

Northwest’s plan was to use the 747 to replace long-range 707s, giving them significantly more cargo and passenger capacity for revenue growth, as a “frequency-driven” model was not appropriate for the traffic demands of that era, not to mention less-capable air-traffic control and more-cramped airports. And by the late 1970s, 707s would be relegated to just flights from Tokyo to its Asian stations.

From the collection of my good friend, Arthur Na.

Eventually Northwest would place 747s on many domestic routes, so much so that in the early 1980s their radio jingle called them the “wide-cabin airline”. The phase-out of this remarkable aircraft is also a reminder that there used to be a time when even coach service had both comfortable legroom as well as seat width…

The first aircraft to enter service flew a very light schedule to help train flight crews; just out and back from Minneapolis headquarters to New York City. While the timetable called for a June 15 start date, in fact the first flights didn’t begin until June 22, 1970:

- Flight 232 left Minneapolis 12:30 pm, arrived New York JFK 3:59 pm

- Flight 221 left JFK 5:30 pm, arrived MSP 7:19 pm

At July 1, 1970 the pace for that first aircraft picked up, and three more joined the fleet. The aircraft routed in this sequence, taking four days to make a complete circuit, with lots of slack time in Minneapolis for training and familiarization:

Day one

- Flight 203: Depart JFK 9:00 am, arrive MSP 10:47 am

- Flight 232: Depart MSP 12:30 pm, arrive JFK 3:59 pm

- Flight 221: Depart JFK 5:30 pm, arrive MSP 7:19 pm

- Maintenance & training checks at Minneapolis

Day two

- Flight 230: Depart MSP 6:15 pm, arrive JFK 9:38 pm

Day three

- Flight 7: Depart JFK 10:00 am, stop at Chicago 11:17-12:20 pm, stop at Seattle 2:15-3:45 pm, arrive Tokyo 5:35 pm on day 4

Day four

- Flight 4: Depart Tokyo 8:20 pm, stop at Seattle 12:50-2:40 pm earlier the same day, stop at Chicago 8:10-9:10 pm, arrive JFK 11:58 pm

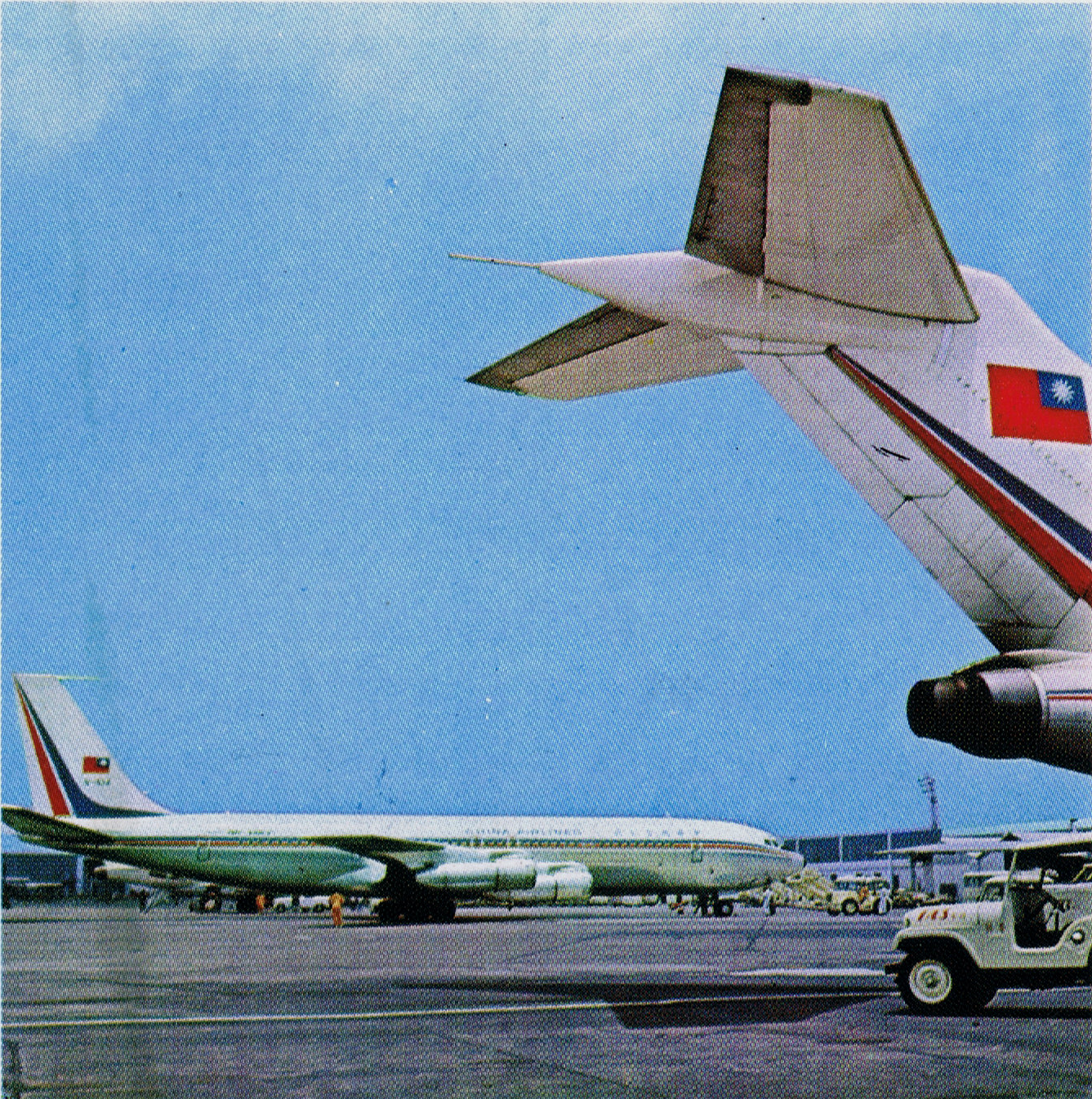

Photo by clipperarctic via Wikimedia Commons, CC 2.0 license

The Minneapolis-San Francisco-Honolulu-Tokyo route was added next, starting August 1 with every-other-day service, going to daily on September 1. The six aircraft in the fleet could then route like this:

Day one

- Flight 9: Depart Minneapolis 8:15 am, stop at San Francisco 9:50-11:00 am, stop at Honolulu 12:55-2:30 pm, arrive Tokyo 5:10 pm on day 2

Day two

- Flight 4: Depart Tokyo 8:20 pm, stop at Seattle 12:50-2:40 pm earlier the same day, stop at Chicago 8:10-9:10 pm, arrive JFK 11:58 pm

Day three

- Flight 203: Depart JFK 9:00 am, arrive MSP 10:47 am

- Flight 232: Depart MSP 12:30 pm, arrive JFK 3:59 pm

- Flight 221: Depart JFK 5:30 pm, arrive MSP 7:19 pm

- Maintenance & training checks at Minneapolis

Day four

- Flight 230: Depart MSP 6:15 pm, arrive JFK 9:38 pm

Day five

- Flight 7: Depart JFK 10:00 am, stop at Chicago 11:17-12:20 pm, stop at Seattle 2:15-3:45 pm, arrive Tokyo 5:35 pm on day 6

Day six

- Flight 10: Depart Tokyo 9:00 pm, stop at Honolulu 9:00-10:45 am earlier the same day, stop at San Francisco 6:20-7:20 pm, arrive MSP 12:35 am on day 1

The 747-200s and even a couple -100s were painted in the"bowling shoe" livery, which remains my favorite.

Final Resting Places

Delta has preserved one 747-400 at their big museum in Atlanta, and the forward fuselage of Northwest’s first 747, N601US, is on display at the Smithsonian National Air & Space museum in Washington, DC.

Also see…

Our airport guide to Minneapolis/St. Paul

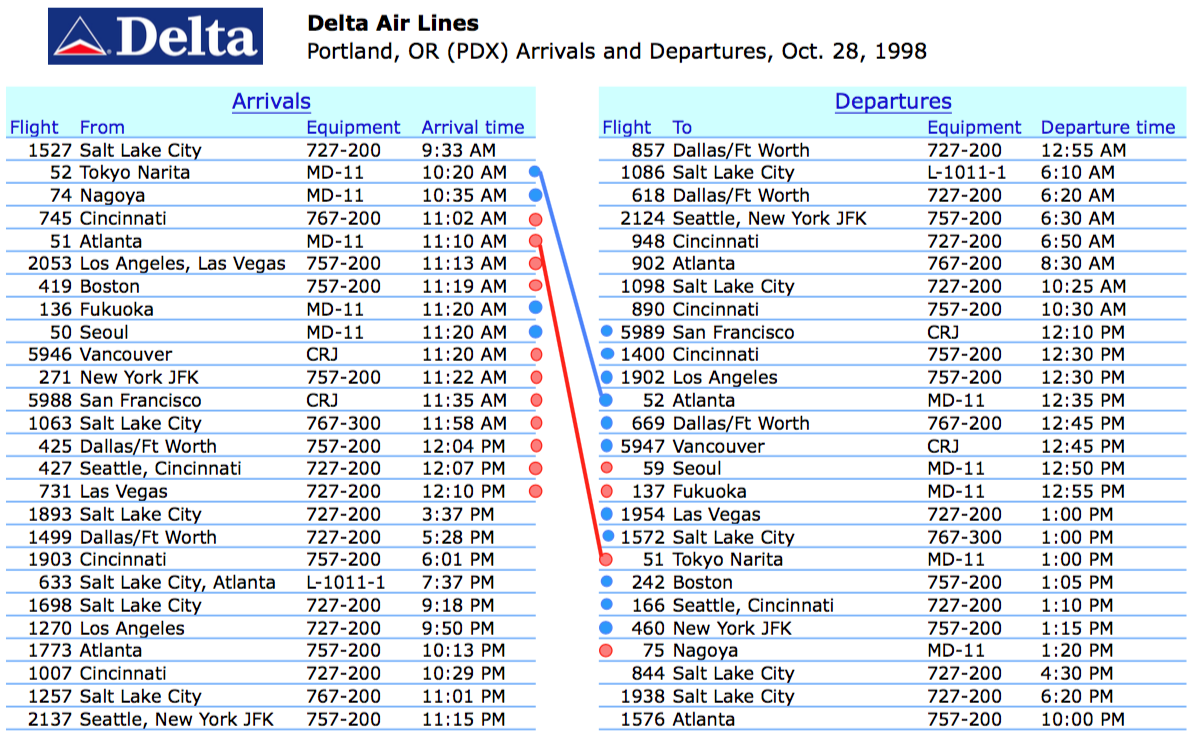

Our article on Northwest Airlines’ “Mall of America” Asian flights