United - Transpacific Inaugural April 1983

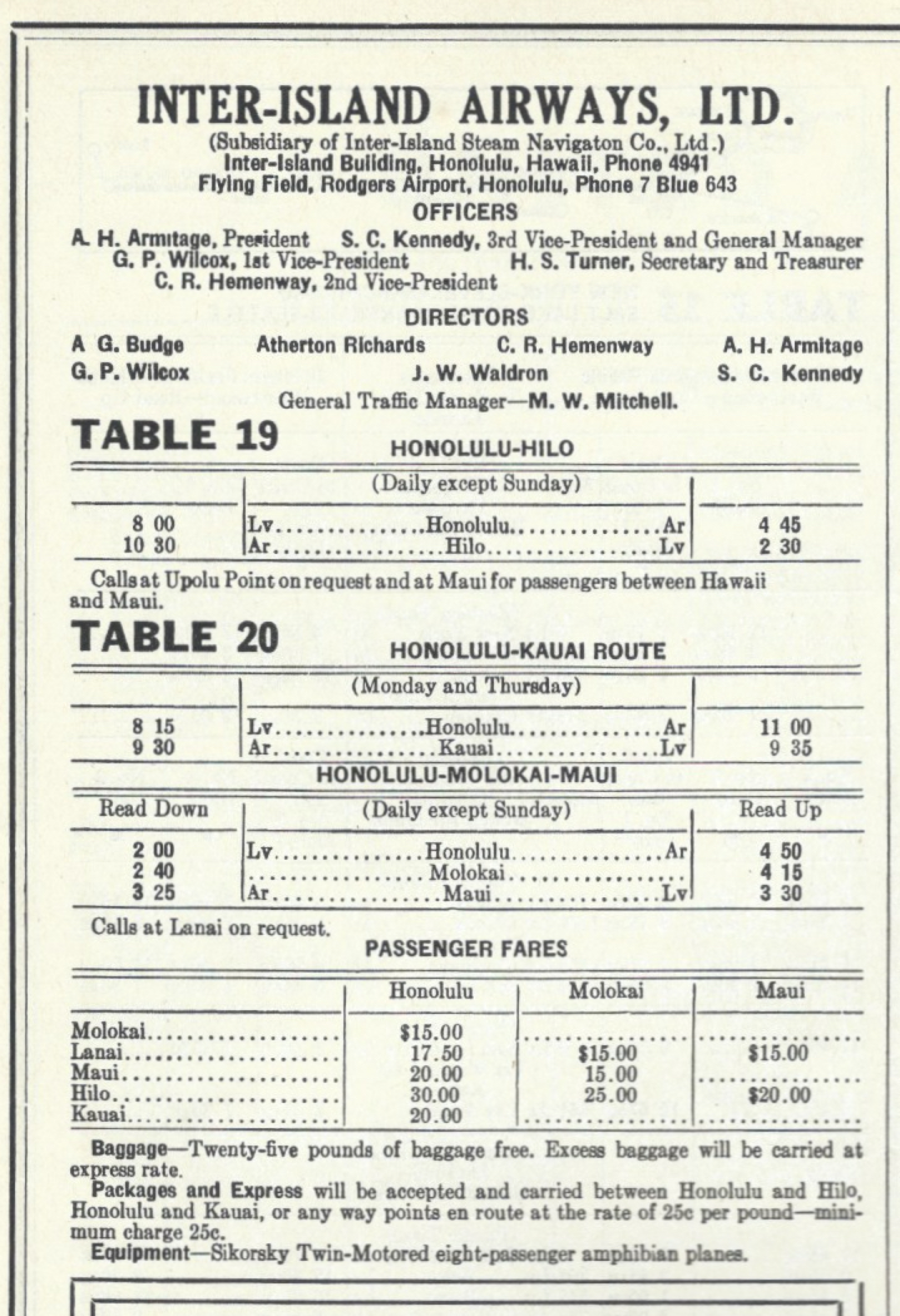

/Executives at United’s headquarters just outside Chicago must have been beyond frustrated in the early 1980s. They were the biggest airline in the U.S., yet for twenty years had been rejected to start international services, time and again. And not having international experience meant they weren’t getting preferential status when new route authorities were opened; a classic catch-22. United had made a big filing with the US Civil Aeronautics Board in the late 1960s to start Asia service, but not only were they rejected, their duopoly with Pan Am to Hawaii was broken apart and they had to compete with Western and Continental on what had been their lucrative Los Angeles/San Francisco-Honolulu traffic!

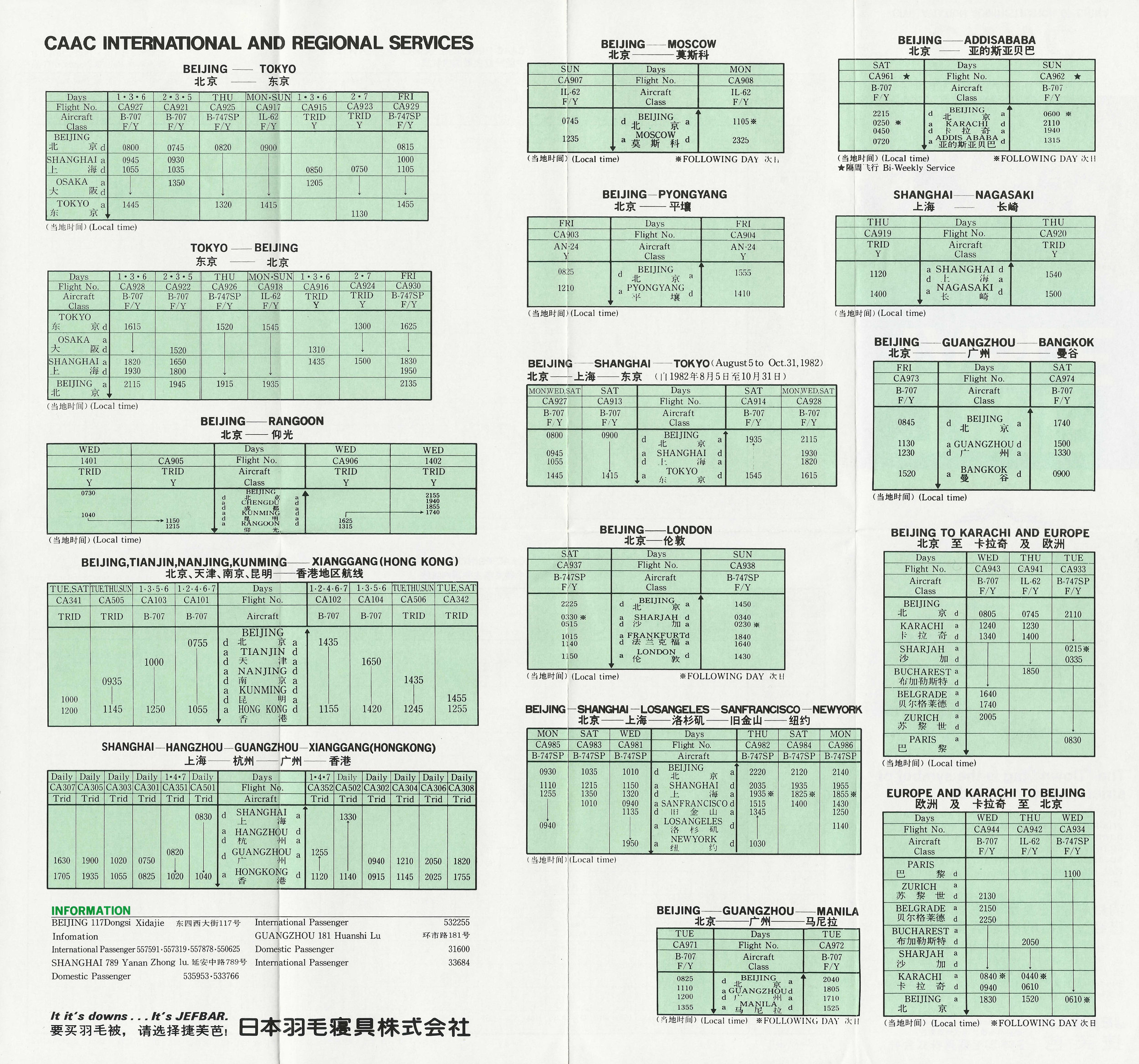

Northwest Orient and Pan Am had Asia; Pan Am and TWA had Europe and the Mideast; Braniff and Pan Am had Latin America. Braniff, Delta, and even little Air Florida had received European routes in the late 1970s – and Braniff had been granted flights to Korea, Hong Kong, and Singapore! When both Braniff and Air Florida had gone out of business, none of the available authorities went to United.

The Japanese government in the 1970s and 1980s took a dim view of letting US carriers expand services to Tokyo any further; while Japan Air Lines still had the largest single-carrier market share across the Pacific, agreements after World War II allowed both Pan Am and Northwest Orient generous “fifth-freedom” rights to pick passengers and freight up in Japan and take them to other points in Asia, and this put JAL into serious competition on both sides of the island chain. While Japan also had similar rights beyond the USA, it was only used on one route to Brazil, so they did not consider the treaty to be well-balanced.

JAL wanted to fly to additional points in America, but was not keen on the prospect of giving NWA or Pan Am an even greater assortment of cities to fly to Tokyo from as a result of negotiations with the US government. Talks went on for years, until someone had the idea to suggest giving United Airlines a route to Japan. United would not have “fifth-freedom” rights … and United’s massive domestic operation could put NWA and Pan Am at a tactical disadvantage. Both elements appealed to the Japanese side, and it was agreed: United would get a Seattle-Tokyo slot, and JAL would get access to both Seattle and Chicago. And Northwest would go from having a monopoly on the Seattle run to having two strong competitors in one blow.

Once the US government agreed on Japan’s conditions, United lobbied hard to pick up landing rights at Hong Kong, where there was an unused daily frequency after Braniff’s collapse. Hong Kong’s government was agreeable, but United would have to fly there without stopping in Japan.

Photo by clipperarctic via Flickr, CC 2.0 license

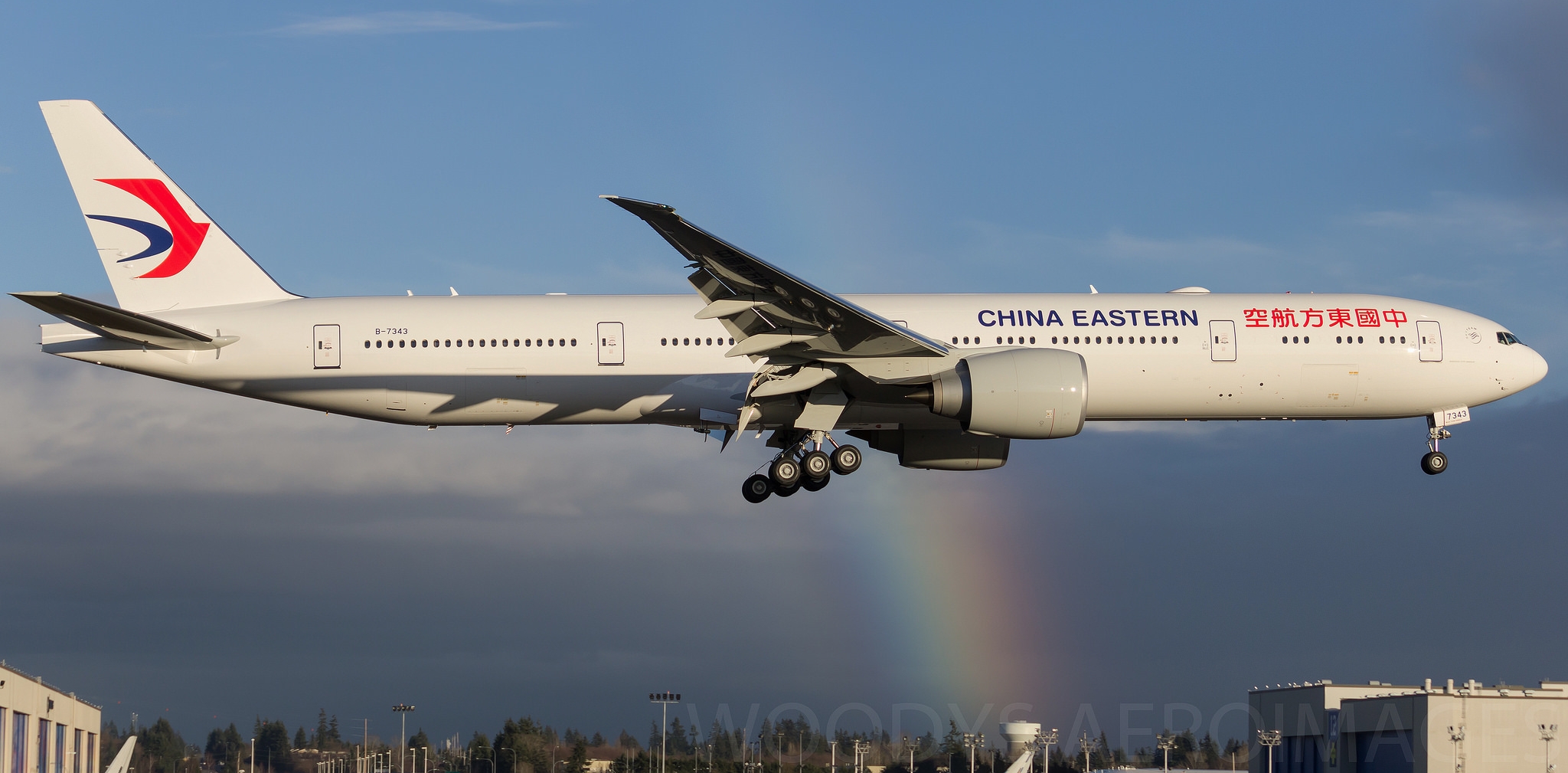

United’s fleet of seventeen 747-100s, delivered from 1970-1972, would be stretched thin on services to Hawaii as well as the Tokyo flight, but the airline’s large and more-recently built fleet of DC-10-10s was the “lightweight” version – enough range to handle flights to Hawaii or from California to New York, but not nearly enough to make Japan, much less another four hours’ flying to Hong Kong.

Photo by contri via Flickr, CC 2.0 license

The solution came from across the northern border: Vancouver-based carrier CP Air was willing to lease United three longer-range DC-10-30s, and this would be just enough to cover the schedule. Plus, United was quite familiar with the DC-10 so crew training for -30 version would be minimal.

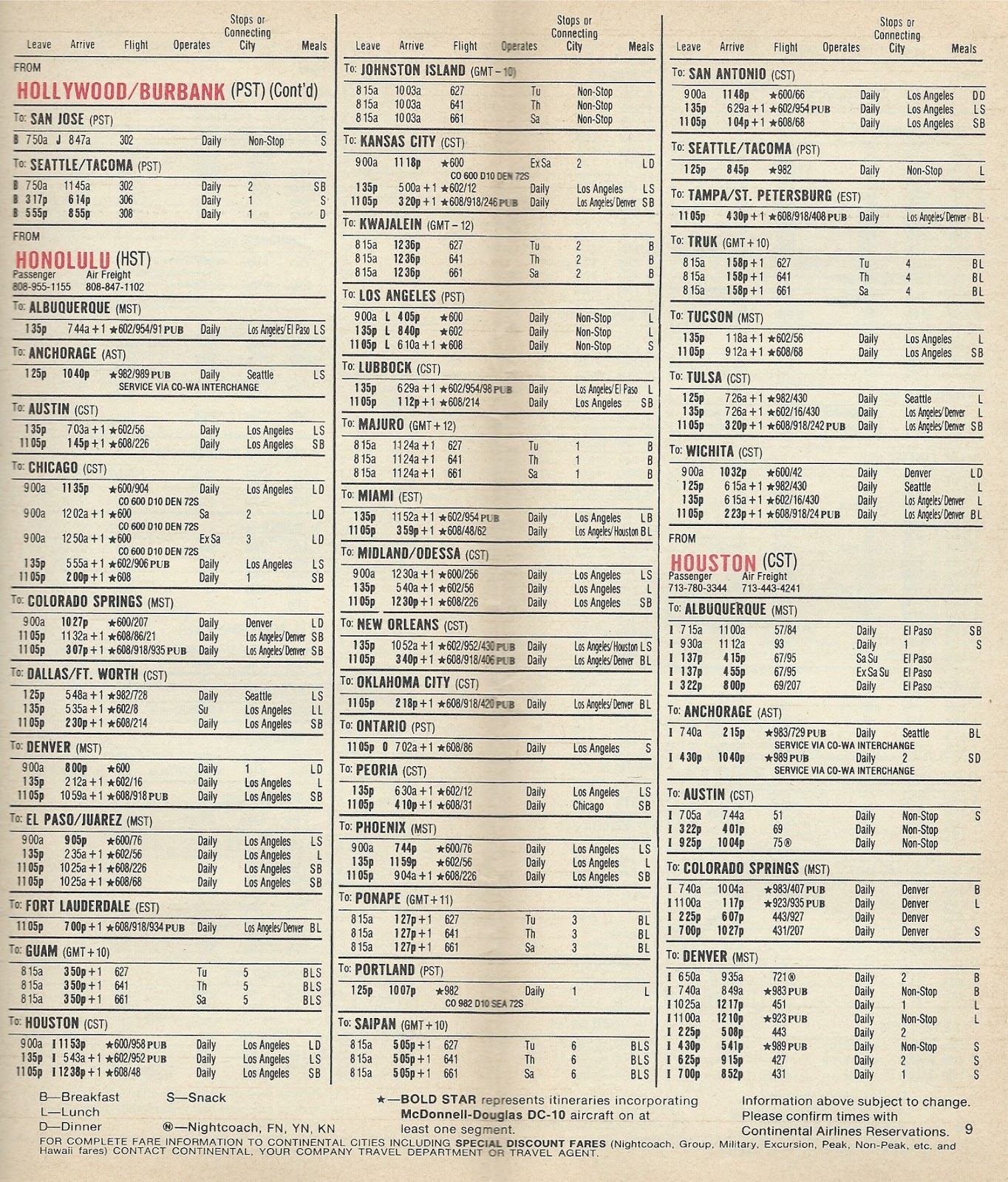

On April 2, 1983, United started its Tokyo service with six weekly nonstops from Seattle/Tacoma, daily except Tuesdays, and on Tuesdays they offered a nonstop from Portland, Oregon, using the 747-100 on all flights. The aircraft would sit at Tokyo-Narita for about four hours before returning to the USA. Both the outbound and return flights terminated at Chicago-O’Hare.

Click to enlarge this route map

Then on May 28, 1983, United began Seattle-Hong Kong nonstops with daily frequency, with both inbound and outbound flights terminating at New York-JFK. The DC-10-30 would arrive Hong Kong’s Kai Tak airport at 6:15 pm and not depart until 1:45 pm the next day – while HKG was happy to have United fly there, the one-runway airport had severe congestion and these were the best times United could get. But even if UA could get a later landing slot and a morning takeoff slot, they’d still need three aircraft to run the routing, and the arrivals and departures at Seattle worked well for connecting traffic from across United’s system, as they had a large operation at SEA in the 1980s.

Outside of a few flights to Toronto, Vancouver, Cancun/Cozumel, and the Bahamas, the Tokyo and Hong Kong routes from the Pacific Northwest would be all the prestige international flying United would do for the first half of the 1980s. But in 1985, UA’s management began quiet negotiations with Pan Am that would change the carrier’s fortunes…

Also see:

http://m.csmonitor.com/1983/0328/032837.html

and other weninchina resources - - -

Our Transpacific Flying folder on Pinterest

Our Tokyo-Narita airport guide