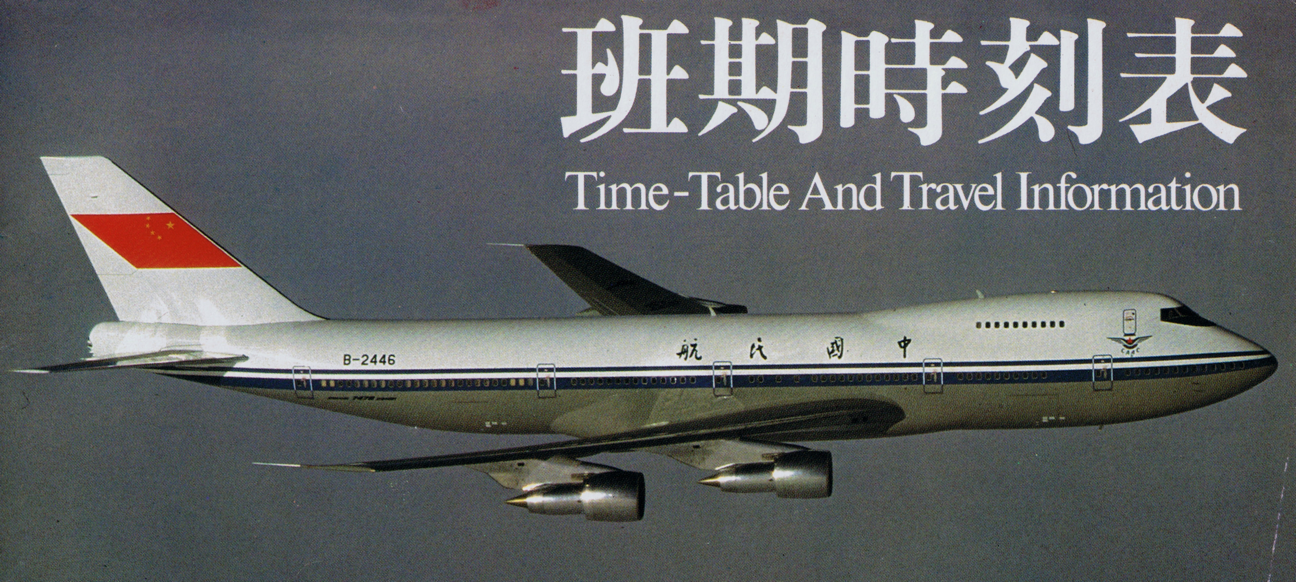

China Airlines - 1971 History Booklet

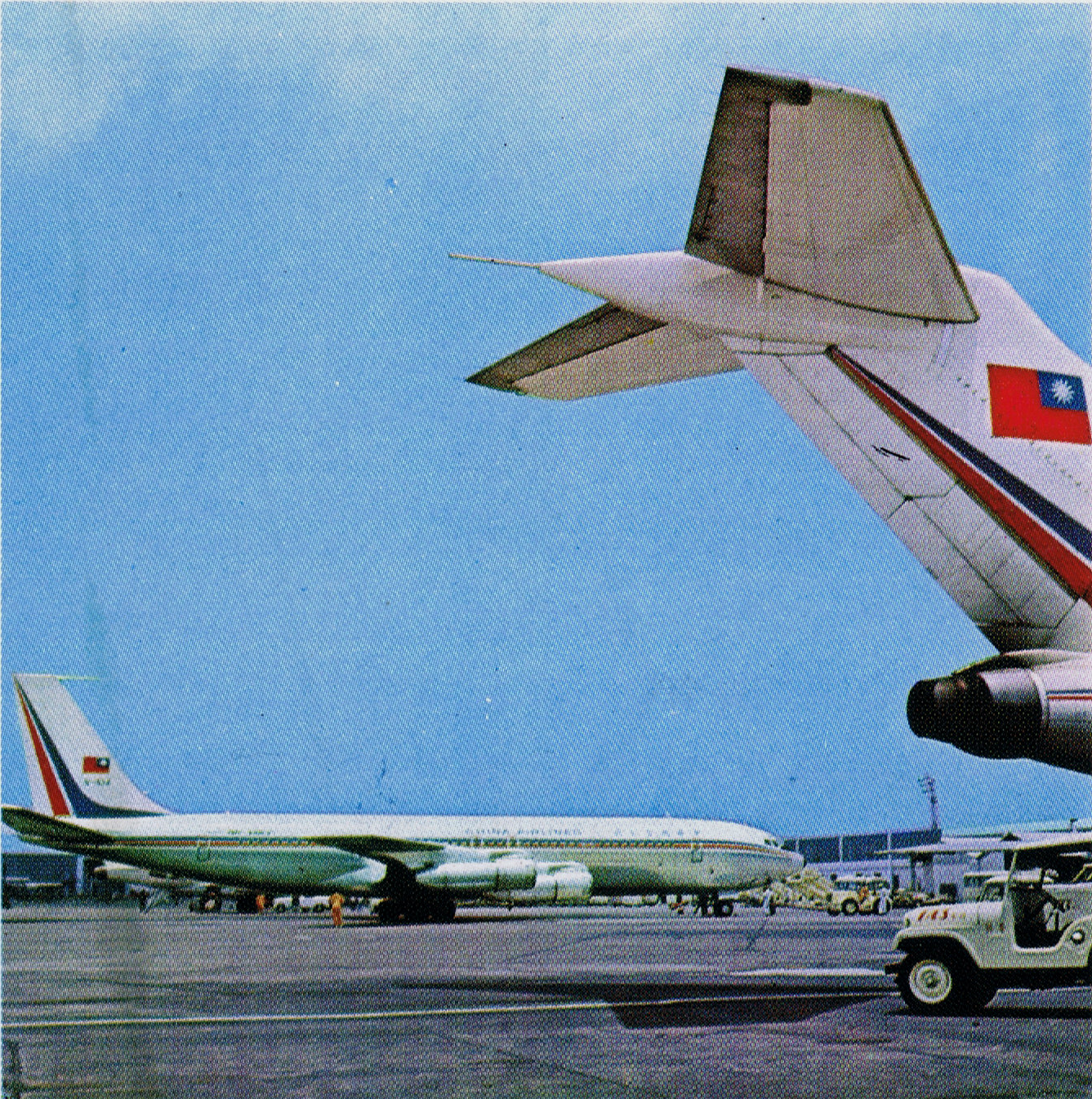

/In celebration of China Airlines' opening of the first Transpacific service into Ontario, California this week, I've posted these scans of a 1971 company history - still a government-controlled entity at this point. CI had launched flights to San Francisco from Taipei via Tokyo in February 1970, and to Los Angeles via Tokyo and Honolulu in April 1971. The Boeing 707 jets used did not have the range to make California nonstop, but even if so the short runways at Taipei's Songhsan Airport would never have supported the long takeoff run that would have been necessary.

These scans are from the collection of my good friend and fellow aviation history buff Arthur Na. Click on each panel for a bigger view!

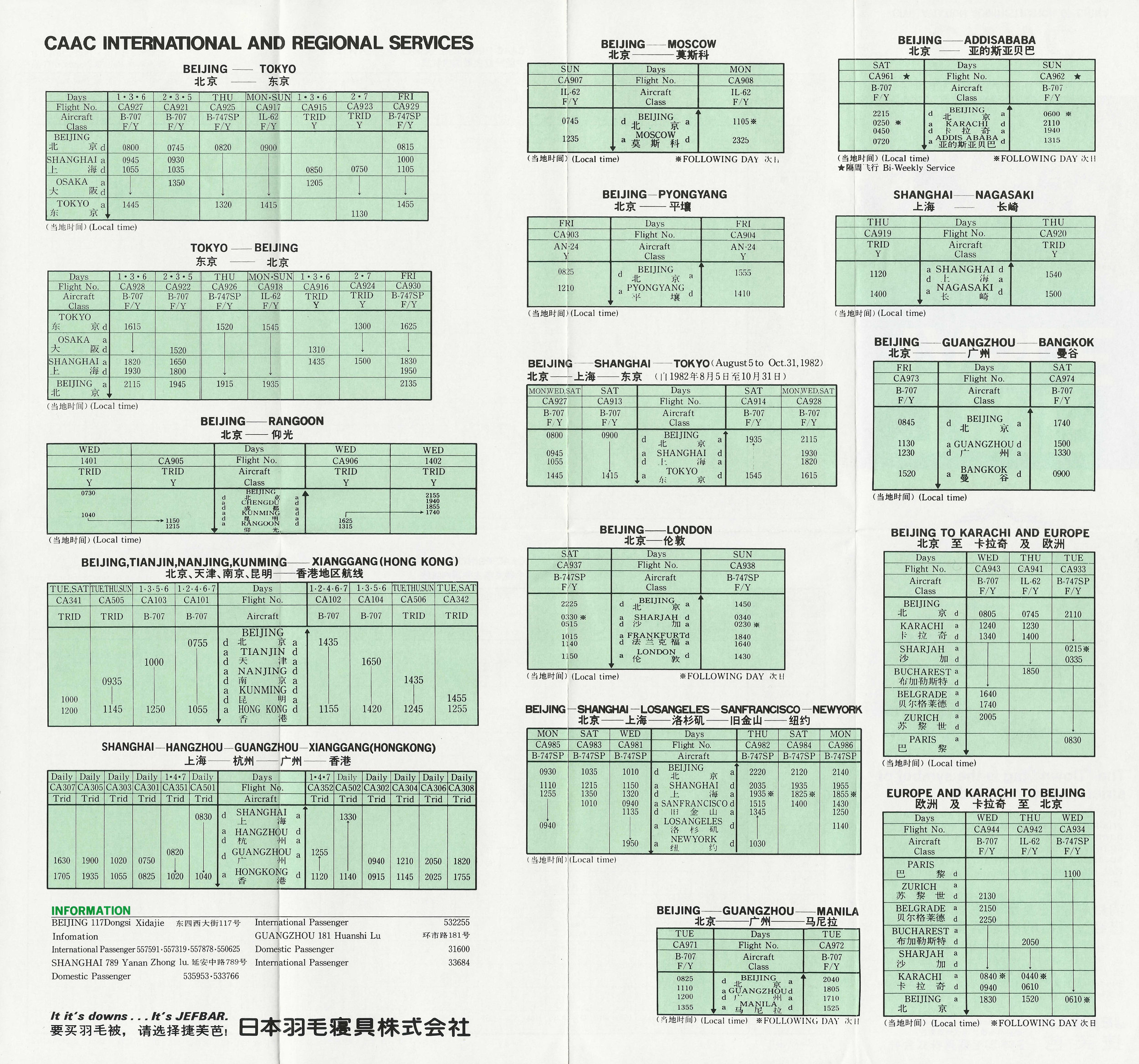

CI would need to pick up an extra 707 after this brochure was printed to be able to cover the Los Angeles route: with how the flights were scheduled, each 707 could make 3-1/2 roundtrips to the USA and back per week. By Fall 1971, San Francisco was served six times weekly, and Los Angeles had four weekly departures.

For good measure, here are scans of the Transpacific services from CI's August 1, 1971 timetable (eastbound and westbound). Passengers arriving Taiwan from the California flights had to spend the night in Taipei to make onward connections because of how late the aircraft arrived; but eastbound Transpacific services left mid-day so passengers from around the region could make same-day connections, and in fact the San Francisco flight originated in Hong Kong using the same aircraft all the way through.