Northwest Airlines’ “Mall of America” Asian flights

/The original North Entrance and mall logo, from the 1990s

Bringing the whole world together under one roof in the late 1990s

Minnesota’s economy had always counted on tourism; as soon as the riverboats and railroads had arrived, resorts and vacation properties opened to take advantage of the state’s many lakes and forests, clean air, four-season outdoor activities, and peaceful quiet.

Even into the 1980s, most tourists to the North came by automobile from nearby states; while Minnesotans love to travel abroad and to overwinter in ‘snowbird’ destinations, the perception of the state as an icy tundra by people on the coasts and in the South made it difficult to attract more inbound visitors from beyond the Midwest.

Those who did make it “up north” discovered Minnesota had world-class cultural venues like the Guthrie Theater, Minnesota Orchestra, and Minneapolis Institute of Art; extensive lake-country resorts like Lutsen, Grand View Lodge, Madden’s, and Breezy Point; big casinos on Native lands; sports – not just the Vikings, Twins, and Timberwolves but also youth soccer and hockey everywhere; excellent zoos; top-notch universities; a good-sized amusement park; parklands everywhere; and excellent shopping … but the state lacked one “iconic attraction” that everyone coming through would need to see.

With the construction of the Metrodome in downtown Minneapolis, and hockey’s North Stars relocating to Dallas, the suburb of Bloomington suddenly had several square miles of prime real estate no longer needed for sports stadiums – right at the corner of two major freeways, and literally at the edge of the airport.

Debates raged through the 1980s about what to do with the property, but in the end a company called Triple Five, who had developed the giant West Edmonton Mall in Canada, was tapped to develop at the time would be America’s largest shopping center.

In August 1992, the Mall of America opened, and Minnesota had its must-see equivalent to the Golden Gate Bridge or Times Square. With a compact but full-featured amusement park in the center, mini-golf course, movie theater, aquarium, four anchor department stores on the corners, and three full rings of stores around the sides, it was easy for families to spend a full day there, and its prime location made it an irresistible stopover for folks on cross-country drives or having long connections at the airport.

And despite predictions of its irrelevancy and predictions of failure, the MOA thrived by mixing entertainment with retail. In 2016 over 40 million visits were made there, and the complex has been remodeled and expanded, adding hotels and even an office tower, with additional expansion phases in the works.

The Mall of America features concerts, cultural festivals, and enthusiast gatherings throughout the year.

With worldwide attention came the realization that food and clothing were quite affordable in Minnesota, and that the Twin Cities were packed with attractions and activities to easily fill a long weekend or even a full week’s vacation. Northwest Airlines, the dominant carrier at Minneapolis/St. Paul International Airport and an early sponsor of the Mall of America, offered domestic vacation packages which proved quite popular in the mid-to-late 1990s. This led to Northwest offering package tours to overseas visitors…

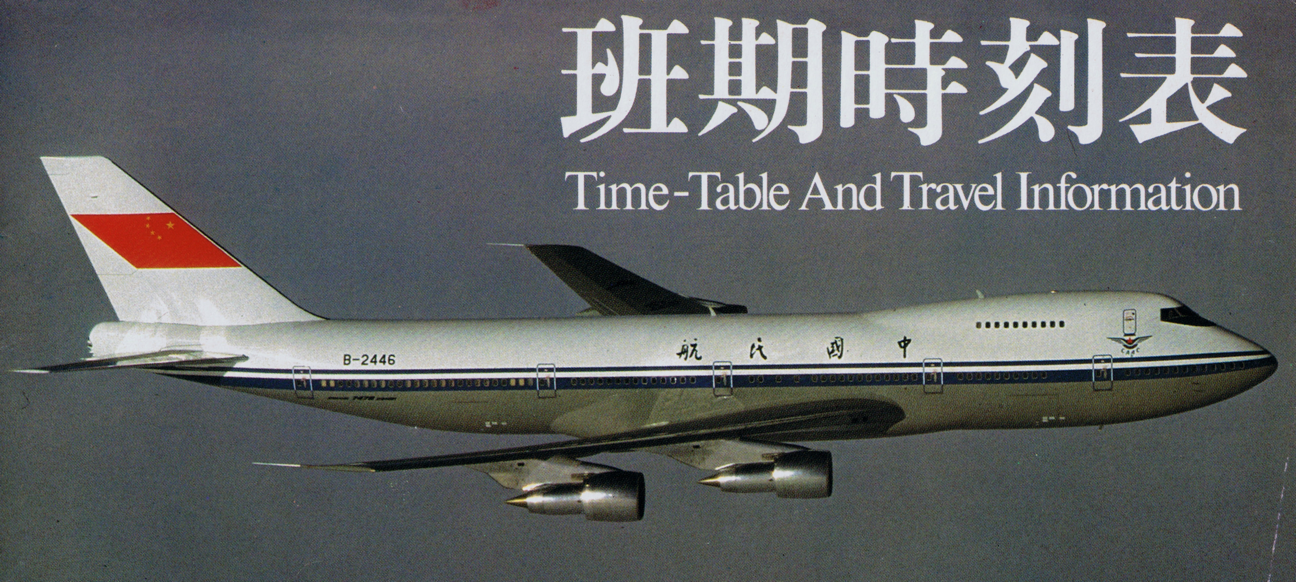

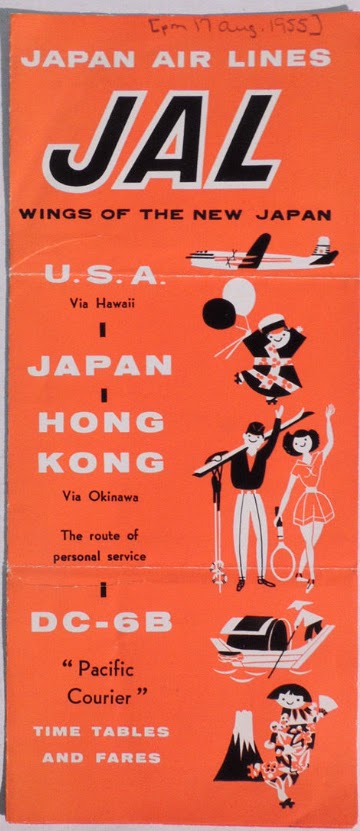

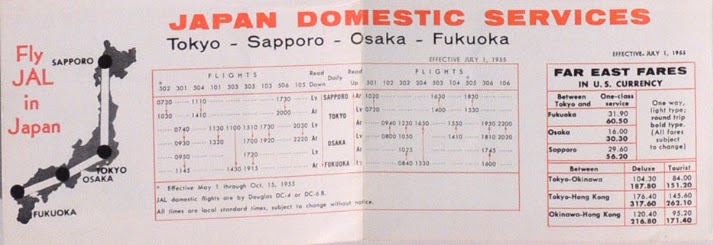

Even in the early 1950s, Northwest was running flights from their headquarters in Minneapolis all the way out to their mini-hub operation in Tokyo, but those were multi-stop flights and passengers had to clear Customs in West Coast cities. These through-flights between MSP and Tokyo came and went through the 1970s and 1980s (sometimes running through California, Hawaii, or Seattle), but after NWA’s 1986 merger with Republic, they made Flight 7 (westbound) and Flight 8 (eastbound) a daily 747 service via Seattle.

Photo by Andrew W. Sieber via Flickr, CC 2.0 license

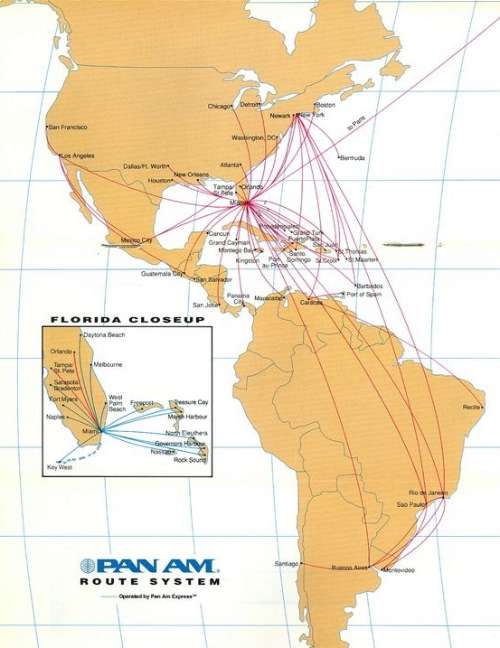

Even though Minneapolis was its major hub, NWA had been running a Tokyo-Chicago nonstop since the 1970s and they were reluctant to give up that prestige route, because if they did, surely United or American would pick up the lucrative Transpacific traffic from their respective O’Hare hubs. And United had become a serious competitor, after buying Pan Am’s Pacific routes.

But after the Mall of America opened and had started demonstrating its ability to draw tourists from beyond the Midwest – and with the construction of a dedicated Customs facility in the main terminal of MSP Airport – the time had come for Northwest to combine two of its strongest network elements and finally begin nonstops to Asia.

This would allow Northwest to offer package tours to shoppers and families with the promise of not having to connect from international to domestic flights in confusing Los Angeles or San Francisco, with a quick and easy Customs line and short light-rail hop from the MSP Airport to the Mall of America.

The flights

From November 1995, Northwest started a Saturday-only nonstop in both directions to its Tokyo hub, supplementing Flights 7/8 via Seattle. Westbound, this was Flight 19, leaving MSP at 1:30 pm and arriving Narita at 5:05 pm Sunday. Eastbound, Flight 20 left Narita at 3:05 pm and arrived MSP at 1:00 pm the same day.

By September 1996, it was clear this service had met its objectives as Northwest increased its frequency to three nonstops per week, and finally to daily by December 1996. Flights 19/20 were also extended out to Singapore, allowing same-plane service from Minnesota all the way to Southeast Asia.

Northwest Airlines publicity photo

1997 was Northwest’s 50th anniversary of service to Asia, and they made a big celebration of it across their system with banners, parties, and special aircraft paint schemes. They started service to Mumbai and Delhi in India, and they also added two more Transpacific flights out of Minneapolis:

Osaka nonstops began in April 1997 with 3-per-week service, using Boeing 747-200 equipment. Westbound, this was Flight 95, departing MSP at 9:20 am and landing at Kansai Airport 1:40 pm the next day. Eastbound, Flight 24 left at 1:50 pm and arrived MSP at 11:45 am the same day.

And finally, nonstops to Hong Kong (the longest route in their system at that time), using a brand-new 747-400, began in October 1997, again with 3-per-week service. Westbound Flight 97 left MSP at 12:45 pm, arriving HKG at 5:15 pm the next day. Eastbound Flight 98 departed Hong Kong at 10:00 am and arrived MSP at 10:30 am the same day.

Photo by Aero Icarus via Flickr, CC 2.0 license

As exciting and groundbreaking as these services were, however, they would not last.

Why did the flights end?

Certainly not because of any decline in the popularity of the Mall of America, or any general decline in the economy: this was still before the events of September 11, 2001, and business and tourism in the US was thriving.

Rather, it was the success Northwest was having from its long-term investments that caused these routes to be cut, plus planning for the airline’s future, and deploying its assets where it could earn the best return:

Northwest’s giant new terminal at Detroit was nearing completion and would open in early 2002 – a mile-long concourse, purpose-built to funnel Asian and European jumbo-jet traffic efficiently and at low cost onto short-haul hops to the major population centers of the Great Lakes and Northeast USA. The Minneapolis airport could only handle a handful of DC-10 and 747 arrivals, whereas Detroit would be able to tackle a dozen at one time, if need be.

Their fleet of then-brand-new Boeing 747-400 jets was coming fully on stream. These birds truly excelled at long-haul flying; the farther the better. And they were exceptional at lifting belly cargo – where Northwest could earn excellent returns in service to the auto industry around Detroit. Minneapolis did not have the depth of nearby cargo customers.

The 747-400 fleet was able to start replacing the older, fully-depreciated 747-200s. The -200 series was a miracle aircraft in the early 1980s, making flights like New York-Tokyo a profitable journey, but it was less fuel-efficient and needed more maintenance than its new sibling, and required a 3-person flight crew. The -400 only needed two pilots on the flight deck, and could carry considerably more. NWA decided not to invest in upgrading its -200 fleet and actually started retiring some of them. Without up-to-date seating (especially in the front of the cabin) and electronics, the -200s were eventually relegated to routes that did not have heavy premium traffic: the tourist-heavy runs between Japan and Hawaii.

So Northwest’s fleet plan, real estate investments, and crucial freight business were optimized around Detroit. And the airline wanted to put its new long-haul aircraft on routes where they could sell a lot of high-fare seats and full pallets of cargo, because those two elements were key to profit. People taking shopping trips may have been numerous, but they were not the kind of customer who would buy a high-profit-margin World Business Class fare.

There were other factors, as well:

The Hong Kong route ended by November 1998: that city’s new airport had just opened in July of that year, and was still having teething troubles which made life difficult and unpredictable for all carriers, but especially those with only one or two daily flights. NWA’s daily morning departure to Tokyo from Hong Kong at 9 am did mean staff could be utilized for its 10 am, 3-day-a-week Minneapolis departure – but the arrival times could not have been more awkward: Tokyo landed at 10 pm, but Minneapolis pulled in at 5 pm, which meant NWA needed to schedule two different staff shifts. And it meant the aircraft handling the MSP run sat on the ground for seventeen hours! These two problems made cutting the route inevitable.

Osaka had different circumstances: NWA was attempting to create a mini-hub at that city’s giant offshore Kansai Airport, adding nonstops from Los Angeles, Detroit, and Seattle to its existing service from Hawaii, and then adding Minneapolis. Northwest was by far the largest non-Japanese carrier at Kansai in the late 1990s – but it did not have extensive traffic rights to fly beyond Osaka to other markets like China, unlike their setup at Tokyo’s Narita Airport. The only place Northwest flew onward to from Osaka was Manila, Philippines – while that city generated a lot of traffic to and from America, the country’s poor economy meant its customers were traveling on heavily-discounted fares.

Photo by Contri via Flickr, CC 2.0 license

NWA did forge a code-share alliance with Japan Air System, that country’s #3 domestic airline, which eventually saw NW flight numbers applied to runs from Osaka to key cities like Fukuoka and Sapporo. This could have become a more-significant partnership: Northwest had no ability to offer connections to other Japanese cities through Narita, but with JAS at Osaka, the entire country was available. Plus, JAS was making plans for international expansion and this could also have fed Northwest’s flights to the USA.

That hope ended abruptly at the turn of the century when JAS decided its shareholders would get a better return by merging the company with another airline – and as Japanese law said only a Japanese company could own an airline, that meant either All Nippon Airways or Japan Air Lines (both fierce competitors against Northwest) would win the prize, with JAL eventually taking over JAS.

Kansai Airport’s high costs of handling aircraft did not help the situation, and the massive slowdown in Japan’s economy meant fewer tourists were interested in flying to America to buy clothes, food, and presents. Ultimately, Northwest’s Osaka strategy fell apart and the city was reconnected to Tokyo with a single-aisle aircraft for connections and onward service to Guam.

NWA ran the Minneapolis-Osaka route into October 1998, and brought it back for the summer in 1999 and 2000. The events of 9/11/01, and the JAL-JAS merger, ensured it would not ever be repeated.

Service between Minneapolis and Tokyo-Narita, however, remained steady with a daily nonstop, and even went to double-daily in the mid-2000s. However, Northwest’s bankruptcy in 2006 and merger with Delta in 2008 would bring changes…

Future Asian service for Minneapolis/St. Paul?

Delta’s decision to de-hub the former Northwest complex at Tokyo-Narita was probably inevitable, but the impact on access to Asia for the Twin Cities was severe. As of Summer 2017, Delta maintains a daily nonstop to Tokyo’s downtown airport, Haneda, but the Boeing 777-200 aircraft used on that service is excessive, considering that Delta does not offer any onward connections from Haneda and does not even coordinate service with its SkyTeam alliance partners there (Korean Air offers service to the “downtown” Seoul airport, Gimpo; China Airlines flies to the “downtown” Taipei airport, Taoyuan; China Eastern flies to Shanghai’s “downtown” airport, Hongqiao.) Delta has to fill that 777 with local traffic from the Upper Midwest and Tokyoites wanting to travel to the North Country.

(Haneda is quite convenient for getting in and out of Tokyo, but it isn’t connected to the Japanese high-speed rail network, so no chance of through-ticketing with Japan Rail…)

What could have been: Northwest Airlines publicity illustration

If Delta had re-committed to Northwest’s order for Boeing 787-8 Dreamliners, that aircraft would be perfectly sized for the Haneda operation, but those orders were cancelled. Delta might choose to use their newer longer-range Airbus A330-300s just coming on line (or new A330-900s on order) for potentially better economics than the 777; the worry is that Delta will decide to deploy either aircraft type on other routes and simply discontinue Tokyo service from MSP altogether. At this point Delta has both sought to reassure the Twin Cities of its commitment to Asian service, but at the same time has vociferously complained to the US and Japanese governments about how landing slots at Haneda have been assigned.

Image by byeangel via Flickr; CC 2.0 license

The near-term hope in 2017-2018 comes from the joint-venture agreement that Delta has signed with Korean Air; that company has aggressively opened service to North America. Local business and tourism leaders are hoping to see service to Seoul’s main airport, Incheon – either on Delta or Korean Air metal. Incheon offers several connecting banks to dozens of cities in China, Japan, and Southeast Asia, far surpassing anything that Northwest was able to offer in the 1990s.

In the longer-run, the Twin Cities would like to see more US-China route authorities become available. This may allow a SkyTeam carrier like China Eastern to come in from Shanghai, or Xiamen Air to begin service from another point on the mainland. Taiwan does not have restrictions on the number of flights to the USA, so it might be possible to attract Taipei-based SkyTeam member China Airlines – but they would need to have a tighter relationship with Delta than they do now to draw heavy connecting traffic through MSP.

The chances of a Star Alliance carrier (United, with Air China, Asiana, EVA Air, and All Nippon) or one from Oneworld (American, with Japan Airlines and Cathay Pacific) landing at MSP are frankly slim. Both alliances have massive hubs at nearby Chicago O’Hare, and any flights directly to Minnesota would work against their interest of flying very full and very large aircraft into Chicago.

Image by byeangel via Flickr; CC 2.0 license

MSP may hope to draw service from the new generation of budget carriers in Asia, such as a Hong Kong Airlines or a Jin Air, as they take delivery of longer-range airplanes: their business models may be best-suited for bringing over planeloads of tourists for Minnesota’s winter activities, summer resorts, and of course shopping.

Hong Kong Airlines and Capital Airlines (based in Tianjin) are both owned by the HNA conglomerate – who also owns Minneapolis-based Radisson Hotels – who happens to have a large hotel attached to the Mall of America! There might be new packaged flight & lodging deals for shoppers and families from China yet in Minnesota’s future…

Update 1: August 2018 / The HNA group of companies spent far too much for acquisitions of travel, real estate, and insurance companies around the world and their core businesses in China could not cover the payments - just as the central government in Beijing cracked down on outflows of Chinese currency. So HNA sold off their stake in Radisson Hotels to the competing Jin Jiang hotel empire, also from China. The HNA Group “synergy” hypothesis in the article above fell apart like a rain-soaked newspaper…

Update 2: December 2018 / Delta announced it would begin Minneapolis - Seoul Incheon nonstops in April 2019 to take advantage of their blossoming relationship with Korean Air. Later that month Delta also filed to begin MSP - Shanghai Pudong nonstop service to start in Spring 2020, if approved!

Also see…

http://triplefive.com/en/pages/moa/tourism-facts

http://specialtyretail.com/news/mall-of-america-caters-to-international-visitors/

http://mspmag.com/shop-and-style/what-if-mall-of-america-didn-t-exist/

http://www.startribune.com/mall-of-america-looks-6-000-miles-away-for-more-shoppers/279637882/

http://usa.chinadaily.com.cn/2014-06/03/content_17557887.htm

and other weninchina resources - - -

Our airport guide to Minneapolis/St. Paul

Our airport guide to Seoul-Incheon

Our airport guide to Tokyo-Narita

Our airport guide to Hong Kong

Saint Paul’s “Little Mekong” district, from our Chinatowns series

Our Minneapolis/St. Paul folder on Pinterest

Our Northwest Airlines folder on Pinterest